The rapid rise of Covid-19 has spawned a renaissance in socio-economic thinking about the best way to face the future, as mayors of cities throughout the world search for answers in the face of declining revenues while society demands more urgent help.

Eureka! Amsterdam, the Venice of the North, discovers doughnut economics. With a click of fingers, it abandons the major tenets of the neoliberal brand of capitalism’s insatiable thirst for growth to infinity at any and all costs. This city where capitalism spawned via the Dutch East India Company first issuing shares in 1602 has turned agnostic on 400 years of embedded capitalism.

In the face of a virus that has turned the world into a state of reflection of how to best cope, new ideas bring new hope. After all, the virus has exposed the utter fragility, vast inequity, and incongruity of the engulfing neoliberal machine as conceived under the auspices of Reaganism/Thatcherism over four decades ago. Nowadays, its results are aptly summarized by the universally accepted epithet “The One Percent.”

Meanwhile, Covid-19 has exposed the radical cockeyed dynamics of infinite growth at any and all costs with profits of billions, and even trillions, atop lopsided pyramids of a sick and hungry forlorn bourgeoisie, analogous to late 18th century France when thousands of aristocrats, holding onto their heads, fled the streets of Paris.

Suddenly, out of the blue, doughnut economics to the rescue, as it levels the playing field, dismantling the wobbly pyramid of growth at any and all costs in favor of learning how to “thrive” rather than grow, and grow, and grow a lot more until ecosystems that support life crumble.

The doughnut economy, in contrast to capitalism, takes its cue from nature. Trees grow to maturity and then thrive for years. Trees do not grow to the top of the sky. Similarly, doughnut economics respects the ecological ceiling by focusing on a reduction of ecological overshoot. It’s a new pathway to a better way of life that blends with nature. At first blush, the Great Doughnut is so appealing that 25% of the world’s economy already has it under consideration as a good substitute for capitalism’s commodification of nature.

Today in central Amsterdam a shopper at a local grocery will find new price tags on potatoes, including 6c extra per kilo for the carbon footprint, 5c extra for the toil farming takes on the ecosystem and 4c extra as fair pay for workers. It’s the “True-Price Initiative” creating awareness amongst buyers of true ecological costs of products essential to the city’s official adoption, as of April 2020, of doughnut economics.

An all-important aspect of doughnut economics is attention to the needs of all citizens by building a strong interconnected social foundation. For example, with the onset of Covid-19, the city realized that thousands of residents did not have access to PCs needed to connect with society during a lockdown. Instead of dialing up a manufacturer to buy new PCs, the city collected old and broken laptops from residents, hired a company to refurbish, and distributed computers to needy citizens. That’s a prime example of the Great Doughnut at work.

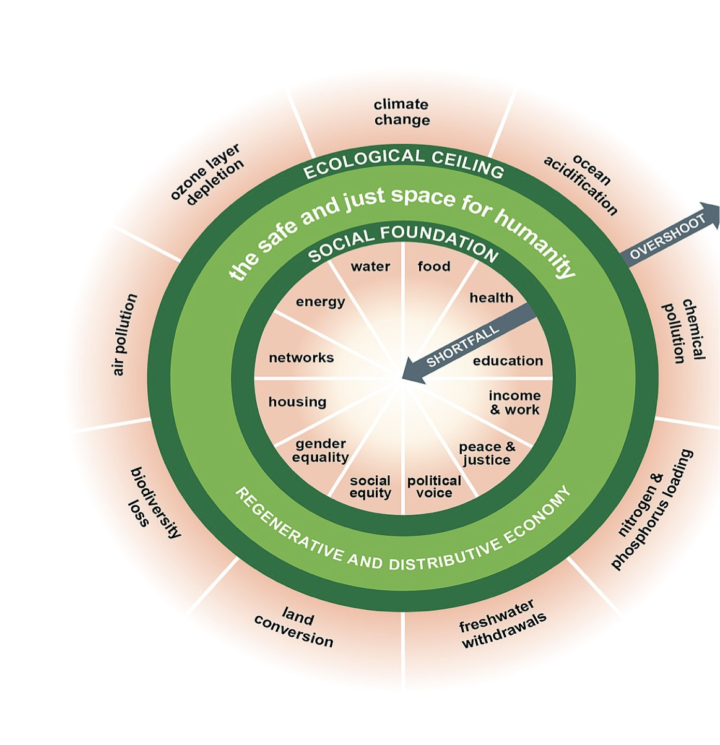

British economist Kate Raworth outlined the theory of doughnut economics in a 2012 paper followed by her 2017 book, Doughnut Economics (Chelsea Green Publishing). It defies traditional economics that she studied at the University of Oxford by focusing on a doughnut symbol of planetary boundaries and social boundaries that define safe and just space for humanity, along with healthy ecosystems, or to put it another way, living harmoniously with nature as opposed to neoliberalism’s indifference and overuse.

According to Ms. Raworth, 20th-century economic thinking is not equipped to deal with the 21st-century reality of a planet on the edge of climate breakdown. Therefore, her theory establishes a “sweet spot” where citizens have everything needed for a good life while respecting the environmental ceiling, avoiding ecological overshoot, like excessive freshwater withdrawals, chemical pollution, and loss of biological diversity to mention only a few.

The doughnut economy is displayed in a visual circular schematic with a green inner circle, which represents a “regenerative and distributive economy that is a safe and just space for humanity” surrounding a list of items that, when in shortfall, need to enter the green doughnut’s “social foundation,” like housing, energy, water, health, income & work, etc. At the outer edge of the doughnut, an “ecological ceiling” lists “ecological overshoots” that threaten the social fabric.

As the world turns, with today’s universality of entrenched capitalism, people in rich countries are living in an ecological overshoot while people in poor countries fall below the social foundation. Thus, both rich and poor are living outside of the regenerative and distributive economy found in the green inner circle of the Great Doughnut.

Amsterdam is working to bring its 872,000 residents into the sweet spot for a good quality of life without putting pressure on the planet beyond nature’s normal rate of sustainability. It’s the Amsterdam Doughnut Coalition as established by 400 locals and orgs within an intertwined network that runs programs at grassroots levels. Thus, the economy sprouts up from ground level rather than dictated from above in lofty boardrooms.

Of more than passing interest, doughnut economics is spreading throughout the world. Copenhagen’s city council is following in Amsterdam’s footsteps. Brussels is following and a city in New Zealand named Dunedin, as well as Nanaimo, British Columbia and Portland, Oregon preparing to roll out their own versions of the doughnut economy. Austin, Texas has the Great Doughnut under consideration.

A sizeable portion (25%) of the world’s economy is already studying what Raworth recognized while studying at Oxford about old school economic supply/demand, efficiency, rationality, and infinite GDP growth but missing a key ingredient known as the web of life. Economists refer to the ecological web of life as an “externality.” Is it really an externality? Such labeling removes the prime source of life from consideration in the fabric of economic development.

Raworth’s theory does not provide for specific policies that must be adopted. That is up to stakeholders to decide on a local basis. In fact, setting benchmarks is the initial step to building a doughnut economy. As for Amsterdam, the city combines doughnut’s goals within a circular economy that reduces, reuses, and recycles materials of consumer goods, building materials, and food products.

In Amsterdam “Policies aim to protect the environment and natural resources, reduce social exclusion and guarantee good living standards for all. Van Doorninck, the deputy mayor, says the doughnut was a revelation. ‘I was brought up in Thatcher times, in Reagan times, with the idea that there’s no alternative to our economic model,’ she says. ‘Reading the doughnut was like, Eureka! There is an alternative! Economics is a social science, not a natural one. It’s invented by people, and it can be changed by people.” (Source: Clara Nugent, Amsterdam Is Embracing a Radical New Economic Theory to Help Save the Environment, Could It Also Replace Capitalism? Time, January 22, 2021)

Of special interest, C40: A Mayors Agenda for a Green and Just Recovery intending to deliver an equitable and sustainable recovery from Covid-19. C40 consists of 96 cities around the world representing 25% of the global economy; it’s a network of megacities. Significantly, C40 has asked Raworth to report on the progress of its doughnut members Amsterdam, Philadelphia, and Portland.

The Great Doughnut overtaking neoliberal capitalism is much more than a simple story. It’s working! It’s brilliant! Yet, the designation doughnut has a peculiar ring that foretells a name change, but maybe not. It’s kinda cute.

A schematic of the doughnut economy follows: