The United States excels at hating taxes, and for good reason. The U.S. government gives you damn near nothing in return for them. You pay them at a higher rate than do billionaires or corporations. Cheating is permitted only if at a sufficiently large scale. And once you’ve paid your taxes, you still have to rush out and pay for everything that your taxes buy you in other countries: healthcare, childcare, education, recreation, retirement, transportation, etc. Pretty soon you’re broke, but all you hear from government spokespeople as they do soaring flips off high dives into swimming pools full of cash for weapons companies is “Sorry, we’re out of funds. Maybe if you donate to our campaigns that’ll help.”

By David Swanson

Who wouldn’t be disgusted?

Well, lovers of World War II, that’s who, if they had any clue where taxes came from. Ordinary people pay taxes in 2021 in the United states that were created to pay for WWII. And, like the military spending, foreign bases, occupations of Germany and Italy and Japan, and even the use of the Pentagon, they were supposed to end some day. Of course, choosing to love taxes when you find out that they’re associated with the number one topic of U.S. propaganda and the very worst thing humanity has ever done to itself in any short period of time is only one option, and not the one I recommend.

Here’s a little background.

Alexander Hamilton’s argument for the power to tax in Federalist #30 was in case anybody wanted some wars. Turns out they did. Between 1789 and 1815, tariffs produced 90 percent of government revenue. But taxes were needed for wars, including wars against protests of the taxes — such as President Washington’s quashing of the Whiskey Rebellion. A property tax was put in place in 1789 in order to build up a Navy (some people in what is now Libya allegedly needed killing for the good of humanity, oddly enough). More taxes were needed in 1798 because of the troublesome French. But taxation really got going with the War of 1812.

The War of 1812 was to be an easy cakewalk kind of war with Canadians welcoming invaders as liberators. But mistakes were made, as they say, and the bill grew hefty. Congress passed a tax program in 1812 that included a direct tax on land, and excise taxes on retailers, stills, auction sales, sugar, bank notes, and carriages. And in 1815, Congress added a new direct tax and restored that controversial whiskey tax as well, plus taxes on all kinds of items, luxurious and otherwise. The idea of an income tax was raised but rejected.

The income tax was brought to you courtesy of that famous act of mass stupidity that is somehow glorious despite most of the world ending slavery without it: the Civil War. The North began an income tax in 1862, and the Confederacy in 1863. This was after the routine promises of a cheap and easy war had worn out their welcome. Both sides were forcing men to leave their homes to kill and risk death, but effectively excusing the wealthy from that duty. Thus arose popular pressure to compel the rich to “sacrifice” financially. Both sides enacted progressive, graduated income taxes, and other taxes as well. The North taxed everything in sight, including inheritances and especially corporations. The financial cost of the Civil War was astronomical, and the veterans’ pension program was the first major social welfare program in the United States.

But with the end of war came the end of support for taxes, and the income tax and the inheritance tax lapsed temporarily in 1872. Taxation returned to primarily regressive forms, taxing consumption rather than taxing incomes at various levels. Advocacy remained strong in the country, its newspapers, and in Congress in the following years to restore the income and inheritance taxes. Major change would not come, however, until World War I and its army of patriotic propagandists. This is from War and Taxes by Steven Bank, Kirk Stark, and Joseph Thorndike:

“The transition from an almost exclusive reliance on customs duties to a substantial reliance on internal revenues, such as the income tax, the estate tax, and excise taxes, could not have occurred without the demand for fiscal sacrifice that accompanied wartime politics.”

What a bargain: you stop taxing foreign goods in order to tax yourself, in order to go kill the people who make the foreign goods — unless they kill you first.

“But this process did not flow naturally from the public mood in support of the war. Rather, for the first time, the notion of wartime fiscal sacrifice was cultivated, marketed, and sold to the American public.”

New taxes were created in 1914, 1916, 1917, and 1918. The income tax was now back in a big way, along with the estate tax, a munitions tax, an excess profits tax, and other heavy taxes on corporations. The munitions and profits taxes were results of an ongoing debate through most of U.S. history over how to tax war profiteering. Until the current century, profiting financially from war was widely considered unacceptable. The draft again served as an argument for taxing the wealthy. Even the U.S. Chamber of Commerce claimed to be “undismayed at the prospect of great taxes,” and pledged “its full and unqualified support in the prosecution of the war.” The 1917 legislation drew 74% of its revenue from taxing the wealthy and another 13% from taxing luxuries.

Following World War I, various taxes were no longer needed. In 1921 and 1924 Congress repealed the excess profits tax but left the income tax in place, rather than adopting a sales tax favored by business groups. The top rate of taxation on income was reduced from 77% to 25%, but that was still more than double where it had been before the war. Meanwhile, the estate tax remained in place, and corporate taxes were actually increased during the 1920s. Taxation and progressive taxation survived the outbreak of peace.

Then came the most glorious war of all, and with it massive taxation for all. World War II spending, taxation, and — of course — the draft, were off and running long before Pearl Harbor. And by the end of this worst catastrophe in human history government funding had been transformed:

“The personal income tax, long confined to the upper strata of American society, became mainstream. Between 1939 and 1945, Congress lowered exemptions repeatedly, converting what had long been a ‘class tax’ into a full-fledged ‘mass tax.’ . . . [B]y 1945, more than 90 percent of American workers were filing income tax returns. At the same time, lawmakers significantly increased tax rates, with marginal tax rates peaking at 94%. . . . By the war’s end, the tax was raising 40% of total federal revenue, making it the largest source of federal funds.”

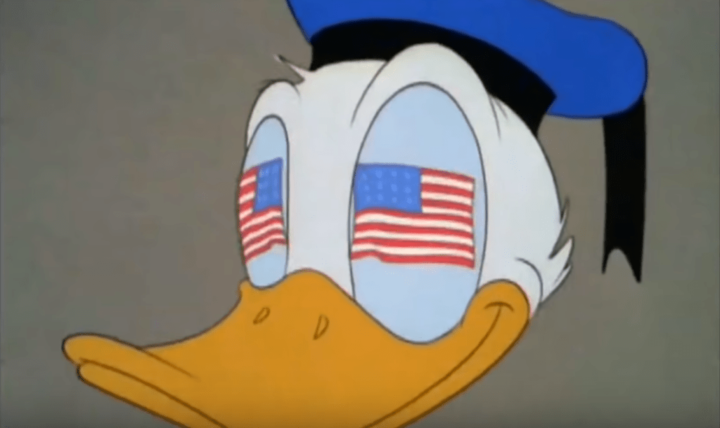

This required a new round of sweet smelling Donald Duck droppings, otherwise known as propaganda. Taxes were renamed “the Victory Tax.” In a Disney cartoon, the narrator warned Donald Duck that “It takes taxes to beat the Axis!” An Irving Berlin song was titled “I Paid My Income Tax Today.” Among the lyrics: “You see those bombers in the sky? Rockefeller helped to build them, So did I!”

In 1943 Congress overrode a presidential veto to shift the tax burden more heavily onto working people. Corporations would never again to this day shoulder the share of public funding that they had in the early years of World War II.

Taxes were reduced again after the war. But again, they were not returned to pre-war levels. The 1948 reduction was the only time taxes have been cut by overriding a presidential veto. President Truman was envisioning a permanent military state while millions of other Americans were hoping war had ended at least for a while.

But in 1950 and 1951, Congress passed new tax bills, including an excess profits tax, to pay for war in Korea, and to return the tax system to roughly what it had been during World War II. Truman won. You lost.

Happy Tax Day!