In the context of the bicentenary, Honduran writer Julio Escoto argues that the Honduran people have an impressive capacity for resistance, and resistance itself implies hope.

“One can enter a stage of illusion with two approaches: the concrete illusion, one says this is my project and I am going to work hard to fulfil it, or the utopia that one knows one wishes for, that one dreams of but does not achieve because that is the utopia, it is something that cannot be realised. The Honduran people are more peaceful than one would like, they should be a little more aggressive, but they have hope, they don’t sink, they don’t get depressed,” Escoto said.

The Honduran writer expresses his admiration for Honduran society, which during 200 years of supposed independence and more than 500 years of external and internal domination, has demonstrated its capacity to resist and survive.

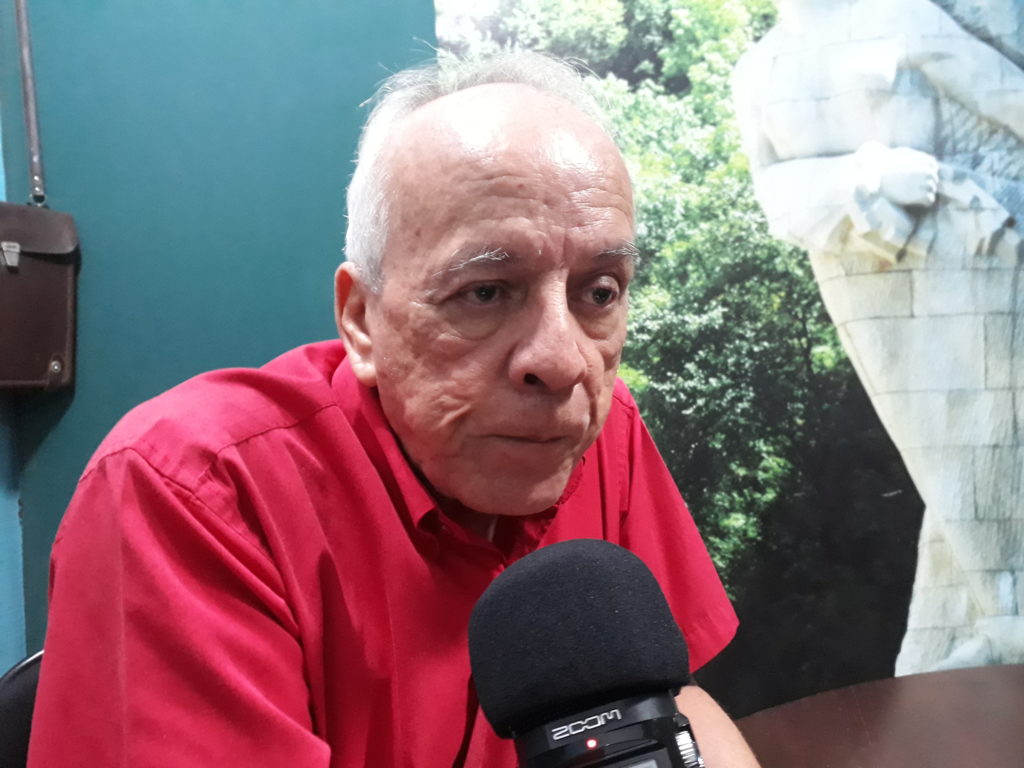

Radio Progreso (RP) spoke with writer Julio Escoto (JE) about the bicentenary and national sovereignty.

RP: How has it survived the pandemic?

JE. Let’s say well, confinement for writers is positive because it makes us work, write, think, meditate, reflect, for me it has been very productive, personally of course, because collectively it is painful to see so many deaths, so many sick people and of course, the most terrible thing, so much abandonment, neglect and so much corruption in the management of the pandemic.

PR. In your reflections, what conclusions have you reached about the situation in the country?

JE. I have to say that I have strengthened my admiration for Honduran society. During 200 years of supposed independence but during 500 years of external and internal domination, the people have proved that they are capable of resisting and surviving.

RP: How do you analyse this resistance at the Central American level?

JE. This is happening all over Central America. If we look at the case of Guatemala, the dictatorships that lasted up to 30 years, if we look at El Salvador, we see criminal presidents like Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, whose number of indigenous people he killed is still unknown. If we go to Nicaragua, which I believe is the most suffering people Central America has ever had, where not only has there been an attempt to sell the country and turn it into a state associated with the United States, but it was also governed by a filibustering North American, had dictators and is currently experiencing a political crisis as well.

If we look at Central America as a whole, it is a people of permanent, constant, day-to-day resistance, which is admirable, worthy of meditation and worthy of saying that we are made of some kind of fibre that will allow us to reach the 22nd century.

RP: What stage of history are we at?

JE. We are entering maturity. We are leaving behind the childhood of belief in political and economic inventions, we are beginning to reflect seriously and to realise that everything we have tried before did not work, not because the systems do not work in themselves but because the men who have governed us, the individuals who have been in charge of the nation have not been capable, they have been unfaithful to the people, unfaithful to the beliefs of the people, to freedom, democracy and reason, and therefore, they have to be changed.

RP: What do you think of rulers who come to power via the ballot box and then adjust the laws to guarantee their continuity, as is happening in Honduras, Nicaragua and now El Salvador?

JE. People need to be convinced that words alone do not change the social situation, you need movement, you need protest and you need action. In these three countries, people have tried to change the situation through words and have not succeeded. In Honduras, with the torch movement, the government rushed to integrate Maccih, but once it was all down, it decided to do away with it.