Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has given new license to the killing of Indigenous people in Brazil. Before he came to power in 2019, it wasn’t clear what he wanted to build, but he knew exactly who and what he wanted to destroy: the Indigenous people and the Amazon rainforest, respectively.

By Nick Estes

“Bolsonaro attacked a woman first, the land, our mother,” the Indigenous leader Célia Xakriabá told me. “We have no choice but to fight back.”

Since becoming president, the former Army captain, who served under the country’s last military dictator, has led an unprecedented war against the environment and the people protecting it. A slew of anti-Indigenous legislation, escalated violence against and assassinations of Indigenous land defenders, and the COVID-19 pandemic have threatened the existence of Brazil’s original people, the Amazon rainforest, and the future of the planet.

Under Bolsonaro’s oversight, about 7,700 square miles (20,000 square kilometers) of the Amazon has been deforested, mostly by fires caused by the cattle and logging industries. The destruction of the Amazon rainforest is pushing the biome toward an irreversible tipping point where it won’t be able to renew itself and making the Amazon uninhabitable for Indigenous people.

Meanwhile, in 2021, scientists found that for the first time the Amazon has been emitting more CO2 than it has been absorbing. The Amazon—often touted as the “lungs of the planet” for the oxygen it creates—seems to be dying faster than it is growing.

But Indigenous people, who call this forest their home, refuse to disappear.

At the end of August 2021, red dust rose like smoke from the pounding feet of some 6,000 Indigenous people marching on the main promenadesurrounded by Brazil’s Supreme Court, Congress, and presidential palace in the country’s capital city of Brasilia. One hundred and seventy-six different Indigenous groups from every region of the country arrived at the encampment of Luta pela Vida (the Struggle for Life movement) to protest against their own erasure. This Indigenous mobilization, which is the largest in history, broke a spell of inviolability surrounding the institutions of power that have for centuries excluded Indigenous people or sought their demise.

“We need a union of Indigenous people,” Alessandra Munduruku from the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, known as APIB, said to me. “Our lives matter.”

They have a champion in Joênia Wapichana, the first Indigenous female lawyer and member of Congress. She’s calling for a “political renewal” of Brazilian and Indigenous rights. And she has helped spearhead the Indigenous movement at a national and international level with APIB.

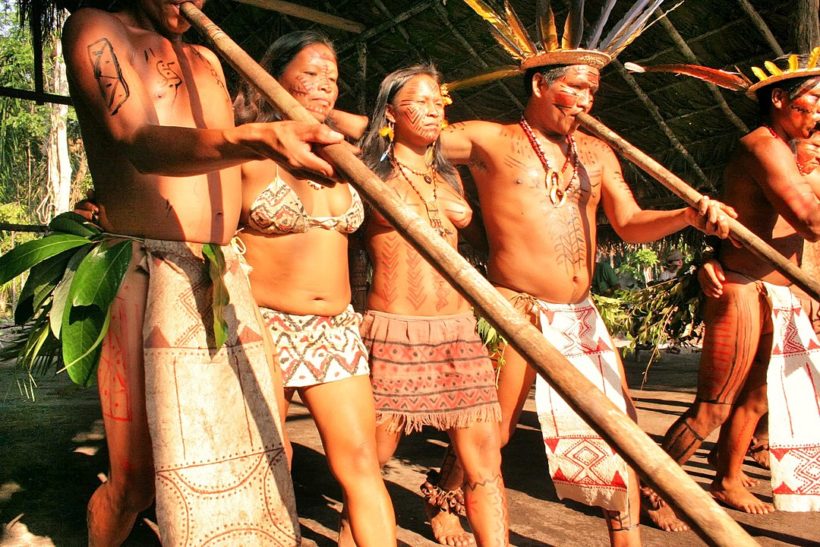

APIB is a powerful unifying tool for the Indigenous peoples of the country. Indigenous Brazilians comprise a small fraction of Brazil’s population—about 900,000 Indigenous people survive today in a country of 211 million—yet they possess a profound human diversity in language and culture not seen in most modern countries. And they are now united in a common cause against Bolsonaro’s belligerence and the powerful forces that brought him into power.

On August 9, APIB filed a lawsuit in the International Criminal Court charging Bolsonaro with genocide. It’s the first time in the history of the ICC that the Indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere have defended themselves, with the help of Indigenous lawyers, against crimes against humanity in the Hague.

“We have been fighting every day for hundreds of years to ensure our existence and today our fight for rights is global,” APIB’s executive director Sonia Guajajara said in a statement.

A coalition of right-wing forces ranging from agribusinesses, the gun lobby, and evangelicals—collectively known as the “bull, bullet, and bible” bloc in parliament—is backing Bolsonaro’s project of destruction of the Amazon and its people.

Soy fields (mostly for animal feed) and cattle herds have replaced lush forestlands and traditional rural communities. Most of Brazil’s food is exported, largely feeding U.S. and European markets. And many Indigenous people blame multinational corporations like Cargill, the United States’ largest privately held company, for their role in drivingenvironmental destruction to produce soy.

Rural landowners, loggers, and miners terrorize and evict Indigenous and traditional communities from their lands at the barrel of a gun. Relaxed firearm and ammunition laws have led to a sharp rise in gun ownership, especially among rural landowners, which has led to a subsequent rise in gun violence. Bolsonaro’s signature finger gun gestures signal support for arming his base.

Much of this influence, including ties to evangelical churches, comes from the United States, a country Bolsonaro and his supporters look to for inspiration.

“It’s a shame that the Brazilian cavalry wasn’t as efficient as the Americans, who exterminated the Indians,” Bolsonaro once lamented.

“Indigenous extermination has already happened in your country [the United States],” Munduruku told me. She sees a similar process unfolding in Brazil. But the connection doesn’t end there.

“At the rate [at which] your country [the United States] consumes soy, it contributes to the destruction of my land,” she added.

The final front of this onslaught is the very legal and political framework protecting Indigenous territories—the 1988 Brazilian Constitution. The Brazilian Congress has been voting on a series of bills that would undo hard-won rights such as protecting Indigenous territories, granting immunity to illegal land-grabbing, and sacrificing Indigenous lands for infrastructure, mining, and energy projects. One of the bills would authorize the president to leave the International Labor Organization Convention’s 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention 169, a major international treaty protecting Indigenous and tribal peoples.

At minimum, APIB and Luta pela Vida are asking the government to respect its own laws and constitution. That’s why a group of 150 Indigenous people burned an effigy of a large black coffin at the steps of Brazil’s Congress on August 27. Scrawled on its sides were the names of the bills aimed at their destruction. The message was clear: Indigenous people refuse to be burned.

On September 1, the Supreme Court began hearing arguments in a case that could lead to either enabling or preventing the usurping of ancestral lands from Indigenous people who were removed from their territories after the ratification of the 1988 Constitution. On September 15, the Supreme Court suspended the case without setting a date to revisit it. APIB claims a positive ruling for Indigenous people would immediately resolve hundreds of land conflicts in the country, and warns a negative ruling could accelerate violence.

What is important to consider is that Brazilian democracy is fragile. As Bolsonaro’s chances for reelection in 2022 dwindle, his supporters calledfor street mobilizations on September 7 to “begin a general cleansing process in Brazil.” The targets of the rally were the Congress, the Supreme Court, and the Chinese Embassy—and Bolsonaro supporters seemed to take their cues from their U.S. counterparts who stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6.

On August 10, Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo Bolsonaro shared a stage with Trump supporters in my rural home state of South Dakota, hoping to cast doubt on the 2022 elections and draw international right-wing support. He was joined by Steve Bannon, who called Brazil’s former leftist leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva “the most dangerous leftist in the world” because his presidential candidacy poses a great threat of undoing what Bolsonaro has done during his presidential term over the last four years.

The following week, in an Indigenous ceremony, Sonia Guajajara designated Lula the “guardian of territories,” a reminder of his obligations to Indigenous people and the Amazon should he become president.

The Indigenous movement goes beyond Brazil and its constitution. “Our [Indigenous] history doesn’t begin in 1988,” was one popular slogan at the Luta pela Vida camp. And the Indigenous struggle is more than recuperating imagined halcyon days that never entirely existed for Indigenous people.

“The future is ancestral,” Guajajara told me. And she’s calling on the entire world to take leadership from Indigenous movements in this time of terrible danger.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Nick Estes is a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. He is a journalist, historian and co-host of the Red Nation Podcast. He is the author of Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (Verso, 2019).