23 November 2021. The Spectator

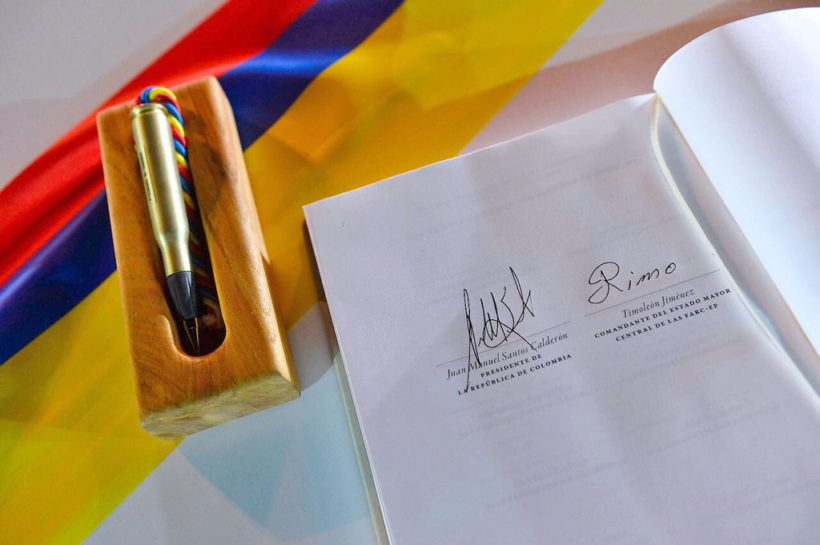

24 November marks five years since the signing of a peace agreement that has so far saved 6,400 lives. The Peace Agreement made the impossible possible, disarmed the world’s oldest guerrilla group and brought us closer to the horizon of living in a country free of violence.

The leaders of the Agreement between the FARC and the Colombian government are invited by half the world to tell how they led the process and how they achieved the most important political event in our recent history. But “nobody is a prophet in their own land”, and the peace that is treated with admiration from the outside, has been trampled on inside Colombia by a sector for which I cannot find adjectives; I will only say that they are not the ones who have to send their children to war, nor serve hunger at the table, nor have they had to flee their land and their roots at midnight. There are those who are convinced and confused; deceived and deceiving; they need war to feel indispensable, to become rich or elected, and hatred clouds their capacity for reconciliation. To feel secure, they kick peace and end up drowning in their narcissism.

In short… We have so many things pending with the Agreement and its signatories! I don’t want to imagine how history will judge a country that was served peace in sheets of paper, and instead of shielding it against human stupidity, allowed it to be mistreated without mercy or conscience.

The Agreement has been wounded in each of the 292 peace signatories assassinated and in each of the 1260 social leaders silenced forever; it has been wounded in the 88 massacres this year; in the displaced, in the atomised communities, in every inch of land to which its legitimate owners have not been able to return.

But peace cannot be reversed and the Accord retains the strength of reason and the work of its promoters; the honour of those who defend it, the commitment to the victims, and a structure that has allowed it to respond to the urgent message of a country overwhelmed by the tachycardia of death.

The Accord has made many Colombians better people and has opened windows where there were only walls and lead. It allowed more than thirteen thousand men and women to exchange rifles for hoes, bullets for laws, and explosives for desks. It has brought to the fore the origins of war, the orphanhood of the camp and the horror of torture of any kind. And, above all, it allowed us to think and feel that reconciliation is possible. We understood that hatred is sterile and that we are much more than a handful of enemies chasing each other on either side of a pile of lies and motives. The Accord taught us that it is better to be river than shore; rather than gravediggers, let us be healers and teachers, and instead of gouging out our eyes, let us learn how benevolence looks.

Five years of an Agreement thought out and worked on so that pain would not continue to take Colombia’s blood sip by sip; five years in which peace has survived despite a disastrous government that did not manage to overcome the stage of the rear-view mirror; five years that have strengthened our commitment to the defence of peace, not even out of altruism but out of common sense; to rebel against the unreason of violence, against the noise of death and the threat of its accomplices.

Five years after the signing, we are able to face the truth; and we all need each other, to tune into the lessons of memory, to make up for lost time and to recognise each other – at last and for a new beginning – in the pending embraces.