During the week the vote took place for the renewal of the board of the convention responsible for drafting the new constitution. The first board had agreed to stay for one term and now it is time for another. The first board was headed by Elisa Loncon, a Mapuche, seconded as vice-president by Jaime Bassa, a constitutional lawyer. They made a good duo, set up the convention and got it up and running overcoming all kinds of obstacles, internal and external.

Among the former, the inexperience and diversity of many people from social movements stood out; among the external obstacles, the government’s lack of interest in collaborating and the closed opposition of a right-wing reduced to a minimum without the capacity to veto because it represented less than a third of the total number of convention members. The latter is unprecedented because for the first time in Chile’s history, the right does not have the upper hand in defining the constitution, and this is what has it on tenterhooks.

The election of the new leadership, like the first one, is by the so-called papal system. Each of the convention members writes down a name, the votes are counted, and if no one has an absolute majority (78 votes), it’s back to square one for a new vote. Between votes, there are breaks of about 15 minutes to talk, negotiate, cook among the Convention members of the different tendencies, and to put names down and put names up. The right, made up of some thirty convention members, can only take a box, voting in a testimonial capacity, watching how the pieces on the chessboard move and eventually supporting whoever inspires the least fear in them.

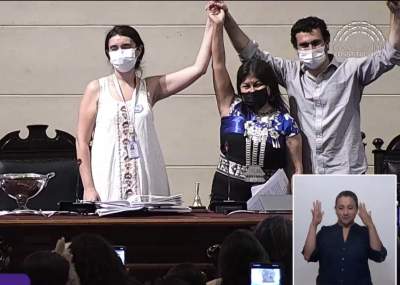

The fact is that on the first day eight ballots passed without anyone emerging with the necessary majority, so that a ninth round had to be held the following day. The new president is María Elisa Quinteros, 40 years old, a dentist, who currently works as an academic and researcher in the Department of Public Health at the University of Talca. Her name only emerged in the end after the fall of the early favourites. Negotiations were the order of the day between the different groups and cliques. The spectacle was not the best, and illustrates the difficulties involved in negotiations between the various left groups, as well as between them and the centre groups that have been forming.

Interestingly, all this “corridor talk” is taking place particularly among those who have been highly critical of the “as far as possible” policies that have characterised the entire transition period so far since the 1990s. These same critics are those who are now experiencing firsthand that the “real thing” is something else, that conversations, dialogues, and cooking between the different interest groups are a daily occurrence and very necessary when it comes to politics, when it comes to democracy.

I would like to take this opportunity to highlight two substantive differences with respect to the process under which the constitution that governs us, the 1980 constitution, was drawn up. One, the 1980 constitution was drafted within four walls, between the hours of the night, without the plebs, the mortals, touching a whistle; and two, its protagonists were all right-wing characters, 100% of them. The result could not be other than a suit tailored to the right, which persists to this day thanks to the locks imposed and which could only be circumvented by virtue of the social rebellion unleashed in October 2019.

From what has been said, it is clear that what is new, what is different, is that within the convention responsible for drafting the new constitution, the right wing is present with a bench that is less than a third of the total number of members of the convention. Its relevance within the convention will be determined by the ability of the other sectors to reach agreement. If the majority of the convention members, who are grouped in the left and the centre, do not agree, then the right can come into play. That is why it is in the water.

At least for the time being, those who subscribe to left and centre thinking have the upper hand, as long as they have the capacity to agree. The latter does not seem easy in light of the different groups that have formed, the temptations in the corridors of power, and the difficulties encountered in putting together a new board, to lead the convention in this new phase of work towards the drafting of the new constitutional charter.

It is striking how things are changing. The new generations seem to be taking the bull by the horns. Our next president will take office at the age of 36 and the new bureau of the constitutional convention will be chaired by a 40-year-old woman. We can only wish them all the best for the benefit of the country.