BRANKO MARCETIC

TRANSLATION: VALENTÍN HUARTE

The biotechnology sector and the government’s commitment to public health now make Cuba the only low-income country to have made its own vaccine. But the island’s doctors are not content with having saved the Cuban population from the pandemic, they propose to extend their assistance to millions of people around the world.

Press coverage of Cuba last week focused on a series of anti-government protests that ultimately did not take place. Much less attention was given to an event that could have a huge global impact: the island’s vaccination campaign.

After a difficult twelve months, in which a too-rapid reopening led to a new wave of virus spread and increased deaths worldwide, the success of the vaccination campaigns transformed the nature of the pandemic. Today Cuba is one of the few low-income countries that not only vaccinated the majority of its population, but did so with a vaccine of its own.

The saga points to a possible way out for developing countries, which continue to struggle with the pandemic in the context of vaccine apartheid. It also proves in more general terms the potential of a medical science that does not respond to private profit.

The safest bet

According to John Hopkins University, as I write these words, 78% of the Cuban population has completed the vaccination schedule. This puts the island in ninth place in the world ranking, above rich countries such as Denmark, China and Australia (the United States, with just under 60% of the population vaccinated, is in 56th place). The turnaround caused by the launch of the vaccination campaign in May revived the country’s economy in the face of the twin crises of the pandemic and the intensifying US blockade.

After a peak of nearly ten thousand infected and close to a hundred deaths a day, the numbers began to plummet. Once 100% of the population had received at least one dose, on 15 November the country reopened its borders to tourism, which accounts for about 10% of its economic income, and recently reopened schools. This makes Cuba an outlier among low-income countries, which together vaccinated 2.8 per cent of their populations. The result is largely due to dose hoarding by developed countries and the zealous policing of patent monopolies, which prevents poorer countries from developing generic versions of all vaccines, ultimately financed by public sector money.

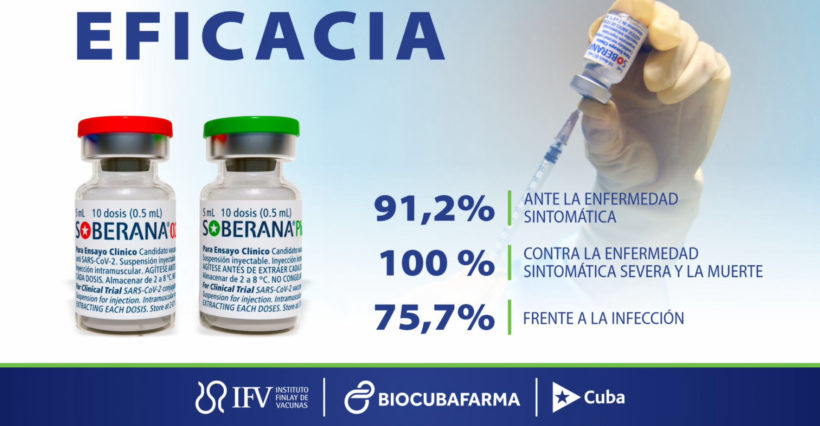

Key in this regard was Cuba’s decision to develop its own vaccines, two of which – Abdala, named after a poem written by one of Cuba’s independence heroes, and Soberana 2 – were officially approved in July and August. In the words of Vicente Vérez Bencomo, respected director of the Finlay Institute, the country made a “safe bet” when it decided not to accelerate the vaccine development process. In this way, Cuba not only managed to avoid dependence on larger allies such as Russia and China, but also guaranteed the possibility of adding a new product to its exports at a time of enormous economic adversity.

The results are there for all to see. Vietnam, with only 39% of its population fully vaccinated, signed an agreement with Cuba to buy 5 million doses and its communist ally recently shipped the first batch of 1 million, with 150,000 as donations. Venezuela (with 32% of the population fully vaccinated) also agreed to buy a batch of the three-dose vaccine for the equivalent of $12 million and recently began administering it, while Iran (51%) and Nigeria (1.6%) signed an agreement with the country to develop their own vaccines. And recently, Syria (4.2%) began discussions with the Cuban authorities about the possibility of doing the same.

The two vaccines are part of a package of five vaccines that Cuba is currently developing. This includes a unique nasal vaccine, which is currently undergoing phase II clinical trials and which, according to one of the scientists leading the research, if proven safe and effective, would be very useful, as the nasal cavity is the main route for the virus to enter the body. In the same package is a booster vaccine, intended primarily for those who received a different vaccine and recently tested on Italian tourists. Since September, Cuba has been in the process of getting its vaccines approved by the World Health Organisation. This would open the door to widespread use.

A different vaccine

According to Helen Yaffe, Senior Lecturer in Social History and Economics at the University of Glasgow, beyond their country of origin, there are many aspects that make Cuban vaccines unique. First, there is the decision to pursue a much more traditional, protein-based vaccine, rather than the more experimental, mRNA-based technology used in the better-known COVID vaccines, which had only a few decades of development prior to the outbreak of the pandemic.

This means that the Cuban vaccine can be kept in an ordinary refrigerator or even at room temperature, unlike the ultra-cold conditions required for the Pfizer vaccine or the sub-zero temperatures required for the Moderna vaccine. “In the Global South, where huge portions of the population do not have access to electricity, [refrigeration] is an additional technological hurdle,” says Yaffe.

Moreover, because mRNA technology has never before been used in children, the difference in vaccination rates in the developed world was considerable (vaccines targeting children under five are still in development). In contrast, Cuba aimed from the outset to create a vaccine that would work for both. This month, more than 80 per cent of the island’s population aged two to eighteen completed their vaccination schedule.

While almost 70 per cent of children in Latin America and the Caribbean have been out of school since September, Cuba has reopened its classrooms. Gloria La Riva, an activist and independent journalist who visited Cuba all year and has been in Havana since mid-October, described the reopening of the Ciudad Escolar 26 de Julio.

“It’s very important for the families,” she said. “Everyone feels immense pride.”

The power of non-profit medicine

There is another important factor that makes the Cuban vaccine special. “The Cuban vaccine is produced entirely by the public biotechnology system,” says Yaffe.

While it is true that in the United States and other developed countries, life-saving medicine is the result of public investment, that does not mean that private companies are not profiting and controlling distribution. But Cuba’s biotechnology sector is entirely state-owned. This means that Cuba has de-commodified a vital human resource: the exact opposite of what we experienced during the last four decades of neoliberalism.

Cuba has been investing billions of dollars in the creation of a national biotechnology industry, especially since the 1980s, when it had to strengthen the sector because of an outbreak of dengue fever and the economic sanctions imposed by Ronald Reagan. Despite a crippling blockade by the United States, which is responsible for a third of the world’s pharmaceutical production, Cuba’s biotech sector managed to thrive: it produces nearly 70% of the 800 medicines consumed by Cubans and eight of the 11 vaccines that are part of the country’s national immunisation programme, not to mention the hundreds of vaccines it exports each year. All the revenue it earns is reinvested in the sector.

Referring to Cuba’s decision to develop its own vaccines, Vérez Bencomo says, “All vaccines that result from scientific innovation are very expensive and are economically inaccessible to the country”.

In any case, Cuba is internationally recognised in the sector. The island won ten gold medals from the United Nations Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) for developing, among other things, the world’s first vaccine against meningitis B. In 2015, Cuba became the first country to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis, thanks to its retroviral drugs and robust public health system.

In that sense, Cuba was able to do the unthinkable: develop its own vaccine and outperform much of the developed world in combating the pandemic, all despite its size, low income and the policy of economic suffocation coming from the other side of the coast. International solidarity campaigns were also crucial. When the US blockade caused a shortage of syringes that jeopardised the island’s vaccination campaign, US solidarity groups sent 6 million syringes, the Mexican government sent 800,000 and China sent another 100,000.

A source of hope

Still, the outlook is uncertain. The use of the vaccines in Venezuela has been challenged by pediatricians’ unions and medical and scientific academies, which use the same argument as other critics: the test results were not subjected to a peer-review process or published in international scientific journals. The Pan American Health Organisation called on Cuba to publish its results.

For his part, Vérez Bencomo blames the international community’s hostility towards Cuba. In an interview in September, he denounced that Cuban scientists are being discriminated against by the big journals, which he accuses of having a long history of rejecting the collaboration of Cubans, even when they later publish similar research by colleagues from other countries, and of acting as a “barrier that tends to marginalise the scientific progress achieved in poor countries”.

This is a very serious denunciation from the mouth of a world-renowned scientist. Winner of Cuba’s National Chemistry Prize and a WIPO gold medal, Vérez Bencomo led a team with the Canadian scientist who developed the world’s first semi-synthetic vaccine, reducing the costs of immunisation against Haemophilus influenzae type B. Later, when, after collaborating in the development of the meningitis vaccine, he wanted to travel to receive a well-deserved award in California, George W. Bush’s State Department blocked his entry to the country on the grounds that his visit was “detrimental to the interests of the United States”. In 2015 he received the Legion of Honour from the then Minister of Social Affairs and Health, who recognised his work and named him a “friend of France” (at the time, Vérez Bencomo refused to give an interview).

Although Cuba’s recovery suggests that Bencomo’s and the Cuban government’s confidence is not misplaced, it may be some time before they receive the stamp of approval from the international scientific community. If that happens, we will add a good argument to challenge the current model of vaccine development, which, following the Big Pharma decalogue, holds that only competition for profit is capable of producing the kind of life-saving innovation the world needs.

Perhaps more importantly, it will help the developing world out of the black hole into which the pandemic seems to have dragged it, and in which it is trapped many months after some rich countries completed their vaccination schedules. Western governments continue to oppose calls from the Global South to go off-patent and enable the manufacture or purchase of generic versions of vaccines. In doing so, they not only harm the majority of the population, but ironically endanger us all, as the Petri dishes the size of entire countries created by their policies encourage the development of new mutations and vaccine-resistant strains. In that sense, we should all be hoping that Cuba’s vaccines prove to be as successful as the scientists who developed them claim.