China’s increasing security measures in Xinjiang reflect its historical territorial vulnerability and concerns over internal stability. Balancing these with its international ambitions and foreign relations will be no easy feat.

By John P. Ruehl

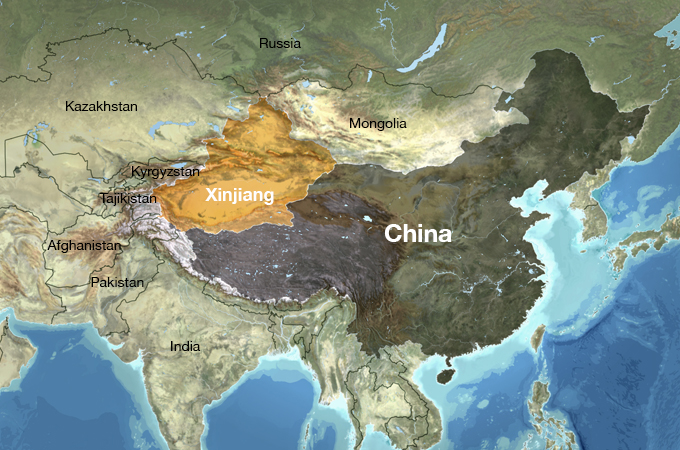

For over a decade, increasing international attention has been focused on China’s treatment of Xinjiang’s Uyghur population. While Beijing is wary of all forms of separatism—Hong Kong and Tibet being its other major concerns in this regard—maintaining an iron grip on Xinjiang is of utmost importance. The Xinjiang region’s natural resource deposits, strategic location in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which involves the creation of economic and trade corridors, and links to the physical defense of China are the most obvious reasons for China to want to keep a stronghold in the region. But the appeal of the Islamic and Turkic nationalism in Xinjiang has also highlighted the difficulty China faces in managing internal stability without upsetting the wider Islamic and Turkic worlds.

Xinjiang’s largely flat terrain made it a primary part of the historical Silk Road route. The region’s geography and proximity to numerous Eurasian cultures and civilizations have also made it a contested land for centuries, with competing narratives over its history and cultural traits. The name Xinjiang, for example, translates to “New Frontier” or “New Dominion” in Chinese, while Uyghur nationalists refer to the region as East Turkestan. Chinese scholars posit that Uyghurs are descended from nomadic Uyghurs from modern-day Mongolia and settled in Xinjiang in the ninth century (joining other groups, including the Han Chinese). Uyghur historians, on the other hand, tend to stress their Central Asian Turkic origins, with East Turkestan their historical homeland.

Regardless of the historical debate over the lineage of Uyghurs, a distinct Muslim and Turkic identity had emerged among portions of Xinjiang’s population in the 18th century when China’s Qing Dynasty reconquered the region. According to historical records, the Chinese campaign split the Uyghur population from the other Turkic groups of Central Asia, which later came under the control of the Russian Empire. Hostility toward Chinese rule in Xinjiang among Muslims from a variety of different cultural backgrounds culminated in the Dungan Revolt from 1862 to 1877, with rebels receiving support from both the Ottoman and British empires. Despite the successful Chinese suppression and pacification of Xinjiang afterward, nationalist sentiment grew within the Muslim-Turkic population, and the term Uyghur began to be used to describe much of the local Muslim-Turkic population around the Tarim Basin by the early 20th century.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 gave way to China’s Warlord Eraand ensuing civil war. Chinese nationalists, communists, Uyghur groups, and Russian/Soviet expeditions all competed with one another for control of Xinjiang. While the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) emerged victorious in 1949, the Kuomintang Islamic Insurgency (1950-1958) across Xinjiang and other nearby regions underlined the threat of political Islam to China’s fragile new leadership. In addition, the Soviet Union encouraged Uyghurs to revolt (as well as Kazakhs living in Xinjiang) to destabilize China after the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s.

In the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Uyghurs’ resistance to Chinese rule of Xinjiang changed in nature. The Soviet collapse allowed independent Turkic states to emerge in Central Asia, inspiring similar nationalist sentiment among Uyghurs. The rise of international terrorism also led Islamic and Turkic militant groups within Xinjiang and across the region to coordinate activities. These developments caused considerable alarm in Beijing, and following public demonstrations by Uyghurs against Chinese rule in the city of Yining in 1995—after “the Chinese authorities [had already] tightened their control over Islam in Xinjiang”—the CCP issued a document called the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Document No. 7 in 1996, which stated that “national separatism and illegal religious activity” should be categorized as “main threats to the stability” of the country in response to the situation in Xinjiang. Thereafter, a “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism” was adopted in the Xinjiang region in 2014, and further public demonstrations were violently suppressed while numerous Uyghur political figures were imprisoned or killed.

However, violent resistance against the policies of the CCP in Xinjiang continued to grow during the first two decades of the 21st century. Knife attacks and bombings increased, while riots in Urumqi in 2009 saw almost 200 people killed. To quell the protests by the Uyghurs, Chinese authorities responded with force and arrests and in 2017 introduced further new and oppressive measures, which included “[detaining] many hundreds of thousands of Uighurs, Kazakhs and other Muslims in internment camps,” according to the New York Times. These camps have been referred to as re-education camps by the state. Mass surveillance, checkpoints, and an increased security presence in Uyghur regions have placed greater pressure on the Uyghur population. The suppression of Uyghur cultural norms and creation of detention centers where more than 1 million Uyghurs have been detained “against their will over the past few years” have drawn the greatest international scrutiny regarding China’s policies in the Xinjiang region, which have been defined as “crimes against humanity and possibly genocide” by several countries, including the U.S. and human rights groups. China continues to restrict international access to the region in the lead-up to the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, leading to some countries announcing diplomatic boycotts of the Olympics.

For several reasons, Beijing is willing to maintain its pressure on Xinjiang in the face of international outcry from the West and certain elements from across the Islamic and Turkic worlds. Xinjiang contains 40 percent of China’s coal, roughly 20 percent of its oil reserves and the largest natural gas reserves, and significant deposits of building materials like marble and granite. As the Chinese economy continues to increase its energy requirements, maintaining access to Xinjiang’s coal, oil, and gas reserves is vital to China’s current and future energy security. Additionally, the region’s location makes it an essential part of the route for China’s BRI project to connect European and Asian economic markets.

The success of greater regional autonomy (or outright secession) in Xinjiang would also not bode well for Chinese attempts to dissuade similar attempts across the country. Hong Kong, Tibet, and even less notable secession movements would be incentivized to increase their own efforts should secessionists in Xinjiang succeed. The loss of Xinjiang would also make China more susceptible to hypothetical future invasions. A more likely and immediate scenario would be challenges to Chinese authority across its border regions, including its violently disputedterritory with India, Aksai Chin, which forms part of Xinjiang and Tibet, and which India claims is part of its Leh district in the country’s Ladakh union territory.

While China’s motives for its tight control on Xinjiang are clear, the consequences of its policies are also becoming more pronounced. Anti-Chinese sentiment in Central Asia has risen in recent years, despite attempts by Central Asian governments to curtail it and ensure continued Chinese economic investment. While many Turkic countries and communities continue to fight among themselves, they are often unified by their disdain toward China’s treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. For China to realize its BRI project, a positive perception of it among the Turkic populations in Central Asian states’ populations will be crucial.

China’s outreach to Central Asian states has been further complicated by Turkey. Owing to its own Turkic heritage, the country has been a primary proponent of pan-Turkism, hosting the first Summit of the Heads of Turkic Speaking States in 1992. Turkey has taken a particularly hard line with China on the issue of Uyghurs, leading to several diplomatic disputesover the last decade. Organizing greater international objection to China’s treatment of the Uyghurs could galvanize pan-Turkism into a viable ideology, with Turkey seeking to take a leadership role in the movement.

So far, China has managed to avoid widespread condemnation from the Muslim world. Beijing has been careful to emphasize its more favorabletreatment of the Hui Muslim population who also inhabit Xinjiang and other Chinese regions. China’s positive relations with major Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, and Indonesia show it has been somewhat successful in its efforts to avoid any backlash from these Muslim nations for its treatment of Uyghurs. But these countries must themselves take care not to downplay the issue, for fear of incentivizing extremist Islamic forces. Radical Salafism has become increasingly popular among Uyghur and other Chinese Muslim populations in Xinjiang, exemplified by the popular support for the Turkistan Islamic Party (formerly known as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement). If Uyghurs feel they have no international Muslim allies, the appeal of extremism will grow further.

While China’s domestic security situation is of paramount importance to the CCP, it remains sensitive to international perceptions of its policies in Xinjiang. In addition, its repressive policies may help instill a stronger and more resistant identity among the local Uyghur population. The CCP’s economic development of Xinjiang will not be enough to significantly erode centuries-old beliefs and cultural loyalties. The historical precedent has shown that foreign states will take advantage of unrest in the region to promote their own interests.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

John P. Ruehl is an Australian-American journalist living in Washington, D.C. He is a contributing editor to Strategic Policy and a contributor to several other foreign affairs publications. He is currently finishing a book on Russia to be published in 2022.