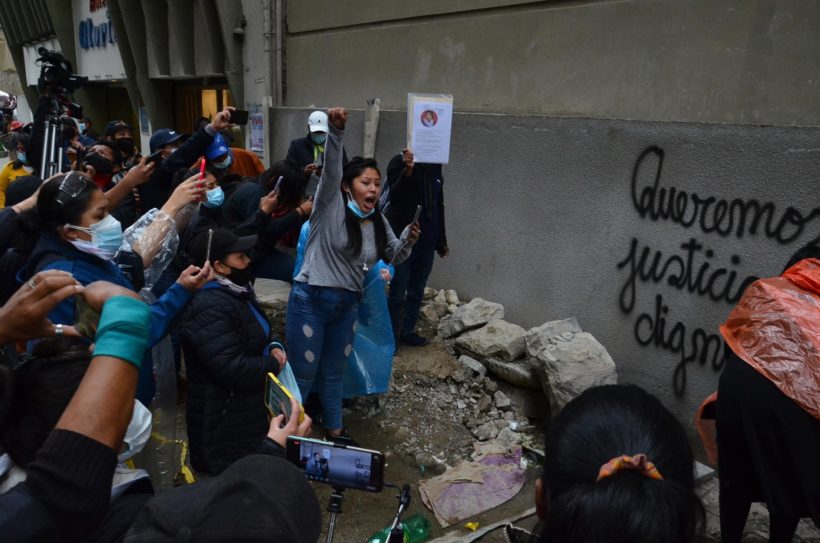

On Monday 31 January, a massive “Women’s March against sexist violence and corruption in the justice system” took place from the Ballivian area of El Alto, through the city of La Paz and ended in front of the departmental court of justice in La Paz, to the cry of “Judges, prosecutors the same filth”. Although the event was organised by feminist activist María Galindo’s “Mujeres Creando” (Women Creating), it should be noted that it was led by the indigenous Aymara women of El Alto, who came to the event on their own initiative. Later, women’s collectives from different parts of the country joined in. The march was led by dozens of relatives of victims of femicide and victims of male violence. It was a historic march because it was attended by Aymara women who live from day to day in their businesses and had to stop working to march.

The march took place in a context of widespread repudiation of the release of Richard Choque Flores, 32, a femicide of at least two women, Iris Villca, 15, and Lucy Ramírez, 17, whose bodies were found buried in his house in El Alto. He is also accused of raping dozens of women, according to the number of contacts traced on his Facebook profile, 77, although the details have yet to be determined. Choque’s mother and wife were arrested for alleged complicity, it is estimated that they could not have been unaware of what was happening in their home.

A central moment of the march occurred when an endless list of names and surnames of rapists and femicides released by the justice system was shown in front of the camera. The data was collected through a call on social networks contributed by several rape victims and relatives of femicide victims. The activist Galindo said: “It is not just the case of this judge, it is a structural phenomenon in Bolivia. We will never again be silent, nor will we forget”.

Since 2015, the femicide offender had been sentenced to 30 years without the possibility of pardon for the femicide and rape of 21-year-old Blanca Rubí Limachi. However, in 2019 he was granted 18 months of house arrest, which he did not serve and no one was watching him. He was arrested for the second time last week and returned to Chonchocoro prison. He also extorted and demanded money from the victims’ families to free them.

His method of recruitment was through calls for “work” on social networks, posing as a woman, he would meet his victims in lodgings and there he would show up dressed as a policeman, plant cocaine on them and, under threat of denouncing them for drug trafficking, he would rape them.

On the other hand, on Saturday 29 January, the accomplice José Luis García Machaca was arrested, who was also under house arrest and had been sentenced to 30 years in prison in 2015 for participating in the same femicide for which Richard Choque was convicted. Judge Rafael Alcón Aliaga, brother of Gonzalo Alcón Aliaga, former president of the Magistrates Council, who freed Richard Choque Flores and another femicide victim who dismembered a woman, was also arrested. The judge is being held for six months in pre-trial detention while the case is investigated.

Luis Arce decrees the creation of a Femicide Commission.

On Tuesday 1 February 2022, María Galindo was received by Eduardo del Castillo, Bolivian Minister of Government, where she demanded the creation of a “Historical Exception Commission” with the aim of counting and compiling the files of cases of femicide and rape at the national level.

On the same day, in response to the women’s mobilisation, President Luis Arce instructed the creation of a “Commission for the Review of cases of femicides and rapes” that had been released from prison. The commission will be made up of authorities from the ministries of the presidency, justice, government, the presidents of the chamber of deputies and senators, the president of the supreme court of justice, the council of the judiciary, the constitutional court of Bolivia, the attorney general’s office and the public prosecutor’s office. In this regard, Luis Arce stated: “Given the worrying situation and conduct of judges and justice operators, we have instructed the creation of a commission to review cases of femicide and rape in which those sentenced were released. The commission must present results within 120 days.

It should be remembered that the country has a “Special joint commission of enquiry into the delay in cases of femicide and violence against women”, the results of which are evident in the light of the facts.

On the other hand, it should be borne in mind that at the beginning of the year the government declared this year as: “The year of the cultural revolution of depatriarchalizing” with the aim of combating violence against women. Luis Arce’s government has been in power for one year, but MAS-IPSP has been in power for 15 years and has a debt pending with Bolivian women.

The feminist agenda, a pending debt of the political class in Bolivia

The case of the femicide and serial rapist freed by the Bolivian justice system is not an exception, but the rule in a conservative society marked by exacerbated racism and machismo. The report of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) presented in August 2021 was lapidary in this regard: “The patriarchal order in Bolivia must be denaturalised because it not only implies a hierarchical order between men and women, but also between indigenous and non-indigenous people”.

Bolivia has highly promoted laws: 1) Law 243 Against Harassment and Political Violence against Women, 2) Law 018 of the Plurinational Electoral Body, and 3) Comprehensive Law 348 to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence, which incorporates the crime of femicide into the penal code with a 30-year prison sentence without the right to pardon. It also has a constitution with a gender and intercultural perspective and is the only country in the world to have re-established itself as a Plurinational State. Bolivia is expected to set an example because it is a reference point for these issues.

However, Bolivia has the highest femicide rate in all of South America according to the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC) until 2019. The case of the femicide and serial rapist in question reveals that the laws that should protect women are a dead letter and are not applied on a daily basis. Let us look at the case of each of the laws mentioned:

1) Law 018 of the Plurinational Electoral Body: although, since the re-foundation of the plurinational state of Bolivia in 2009, women massively entered politics, this happened only in low-ranking positions and low decision-making power in the legislative assembly which is composed of little more than 50% women. The glass ceiling is evident because the presidents of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate are men. Moreover, out of 18 ministries, only four ministers are women and only one of them is an indigenous woman. In turn, during the sub-national elections in March 2021, “the women’s alliance for the democratic and cultural revolution” that make up the MAS, demanded that gender parity in women’s candidacies be complied with. The response they received was zero women candidates for governorships.

2) Law 243 Against Harassment and Political Violence against Women: Segundina Flores, indigenous leader and current Bolivian ambassador to Ecuador, was the face behind the demand for gender parity during the sub-national elections. She was accused of being a “traitor” and of “working for the right wing” for her demands and for questioning the MAS elite, which is made up of white men. On the other hand, the only woman who contested a candidacy for a high-ranking political post with high decision-making power was Eva Copa, former president of the Bolivian Senate for MAS. She demanded to run for mayor of El Alto, the country’s most important mayoralty, but was expelled from MAS on accusations of being “greedy for power”. Copa defied the MAS elite, ran with another party and won with 70 per cent of the vote against the male MAS candidate. Faced with this situation, on 29 December 2020, Esther Soria, former governor of Cochabamba for MAS, denounced on her Facebook account a “strong patriarchy within MAS”.

3) Comprehensive Law 348 to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence: This law incorporates the figure of femicide with a 30-year prison sentence without the right to pardon. The case of the femicide and serial rapist in question shows that it is not enforced by patriarchal justice, but there are also those politically responsible. It also shows that in 15 years of the “process of change”, justice has not been democratised, nor has it incorporated the gender perspective as promised.

Law 348 has a legal trap for women, it unusually allows a violent man to victimise himself and use it to make a counter-denunciation to his victim-wife for “gender violence” and neutralise any investigation that could be initiated by a woman’s denunciation. This could be considered a legal aberration, which is why at the beginning of 2021, under pressure from women, the state promised to reform this law, but everything has remained in a box.

It is unacceptable that a man can use a law that belongs to the women and that was passed specially, to protect women who are raped, this shows the macho conception of “gender violence” of the political class that passed this law with this legal trap. When there is a case of violence from a woman against a man, which by the way are very few cases, it should be conceptualised as another type of violence, never as gender violence.

As a result, the issue of gender violence is not on the political agenda, nor is it on the agenda of Bolivian society, as it is in Argentinean society thanks to “Ni Una Menos” and the united, autonomous and non-partisan work of women who do not organise themselves according to a government, regardless of political colour.