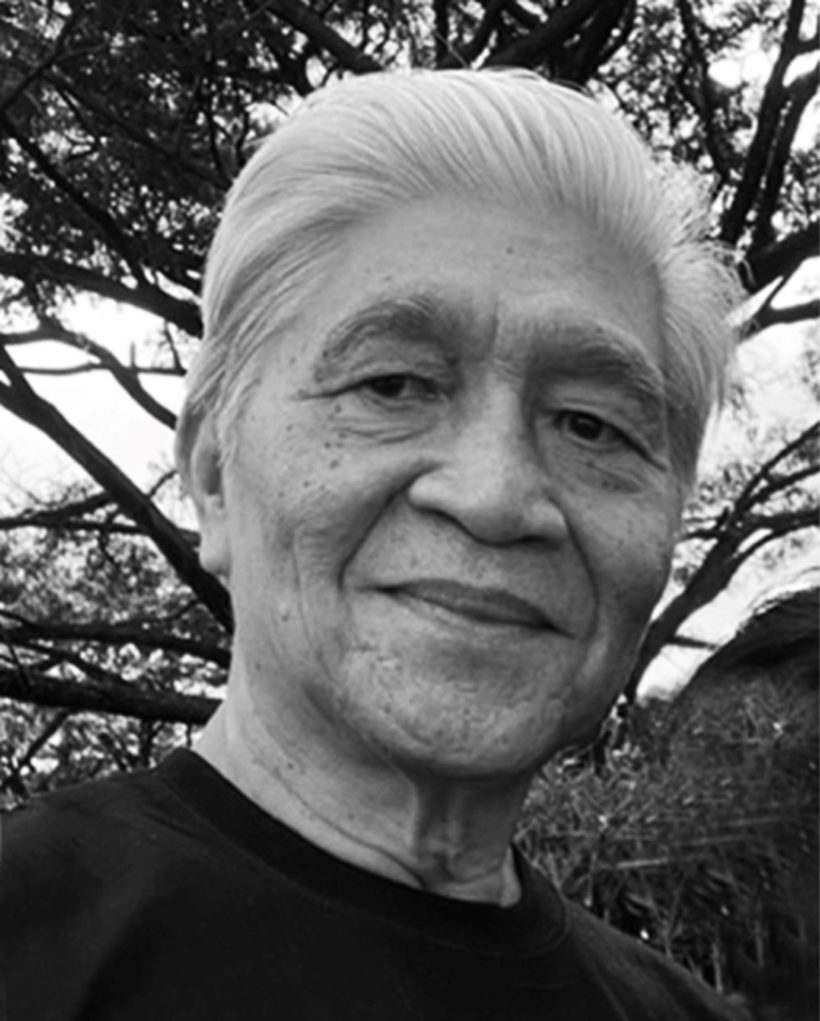

As founder and president of the Education for Life Foundation, Edicio dela Torre synthesizes and applies Paulo Freire’s dialogical and problem-posing approaches, N.F.S. Grundtvig’s folk school, and Filipino psychology and traditions towards grassroots empowerment for social justice, human rights, and environmental protection. A former Catholic priest and political prisoner, dela Torre shares with Pressenza journalist Perfecto Caparas his broad experiences, insights, and ideas on democratization.

Perfecto Caparas: How did you put into practice Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy in the Philippine context? Why did you choose that path? Will you sum up the works that you have accomplished thus far? How was your experience?

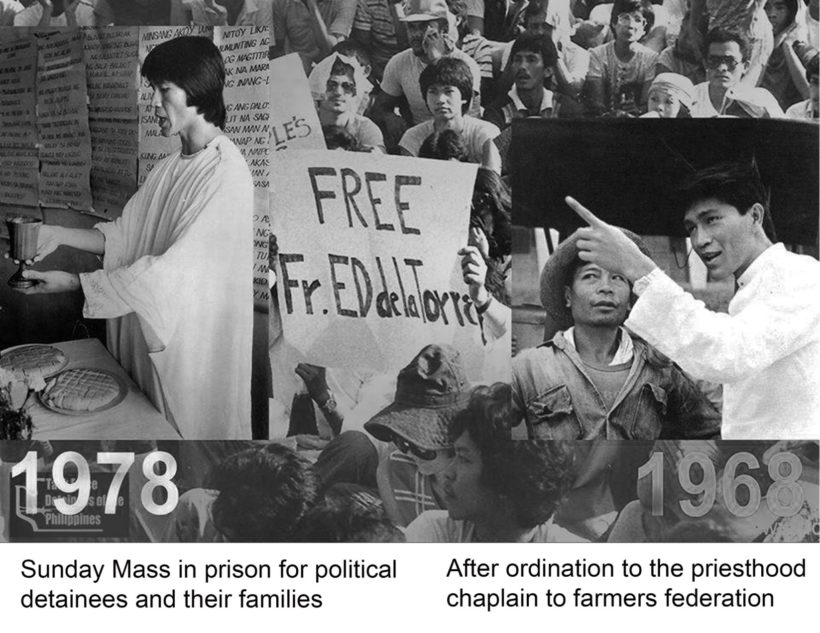

Edicio dela Torre: It was in 1970 that I first read a xeroxed copy of Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. I was a young priest, ordained in 1968 and serving as a chaplain of the Federation of Free Farmers, a Catholic-inspired organization of farmers struggling for land reform. I participated in their education and leadership formation program.

As a priest, I had the tendency to “preach,” which was also the expectation of the farmers. Over time, as we exchanged stories, we both learned to be more “dialogical” in our approach to education and learning.

Hence, Freire’s ideas about “dialogical decoding” spoke to me, together with his critique of a banking method of education. Another Freire method that I practiced is his “problem-posing” approach to education.

These ideas were reinforced when I worked with university students and new graduates whom we mobilized to support the cause of the farmers. They too preferred to dialogue rather than listen to lectures.

Resistance movement

The dialogical approach became even more relevant as our frustrations, due to the lack of positive action by the government, led us to consider and debate the calls from more radical organizations to shift from seeking changes through reforms, and instead pursue the needed changes through a revolutionary strategy.

President Marcos’ imposition of martial law in 1972 hastened the process of our radicalization, and many of us Christian reformers joined the clandestine resistance movement. The authoritarian methods of government and the corresponding need for a coordinated resistance, combined to support the tendency in the movement to employ a prescriptive approach to education and leadership. I remember rereading Freire’s writings which also criticized such “commandist” practices in revolutionary movements.

Political prisoner

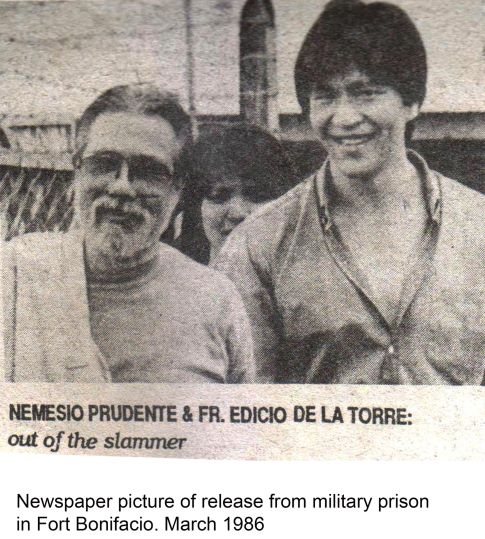

From 1972 to 1986, I was part of the revolutionary resistance. That included spending nine years in various military camps as a political prisoner and one year in temporary exile. Because my main political work was in developing alliances, I benefited from such exposure to appreciate a pluralist approach to politics, and to practice even more consistently the dialogical approach to discussions and decision-making.

Popular democracy

After the restoration of formal democracy in 1986, I was among the former political prisoners and activists from the resistance movement who chose to promote “popular democracy” seeking to navigate a path between accepting the limitations of a restored democracy that was elite-dominated or joining the call to continue the armed revolutionary struggle.

We sought to build alliances among different political tendencies, toward a shared project of pursuing democratization and development “from below” as counterparts to efforts at democratization and development “from above.”

Community organizing and coalition-building

To promote popular democracy and democratization from below, we used a trinity of programs – community organizing in rural and urban areas, popular education, and community leadership formation. To influence democratization from above, we built coalitions that engaged in advocacy actions for sectoral issues like agrarian reform, labor rights, housing for urban poor, and broader national issues like the renegotiation of illegitimate foreign debt, and a peaceful settlement of the armed conflict.

But the context from 1986 to 1992 under the government led by President Corazon Aquino was complicated and turbulent. There were nine coup plots and attempts by military groups, and also many conflicts within the coalition government itself. The failure of the peace negotiations with the National Democratic Front was followed by an upsurge in the armed struggle, and by increased repressive actions by the military. These targeted open legal organizations and persons they considered as subversive.

As advocates of popular democracy, we continued to pursue what we called “conjunctural possibilities” for reform, but we were confronted by the structural limits set by the dominant social and political system. Though martial law had ended, repression continued, including the brutal killings of a number of open legal advocates and critics.

N.F.S. Grundtvig’s folk school

That risky situation prevented my immediate return from a speaking trip to Denmark. That gave me time and opportunity to learn about the Danish folkehøjskole (people’s high school) and the ideas of N.F.S. Grundtvig on “education for life.” He emphasized the importance of the “living word in community.” I was impressed by the role played by his ideas and the folk high schools in the democratization and formation of national identity in Denmark.

When I was finally able to return to the Philippines, I worked with colleagues in the Education for Life Foundation, and its main program – “grassroots community leaders formation for grassroots community empowerment.” This project of popular democracy combined the ideas of Paulo Freire, the ideas of Grundtvig, and ideas from the Philippine tradition of popular education and from Indigenous Psychology (Sikolohiyang Pilipino).

“Fire from below and from above”

During the presidency of Fidel Ramos, the combination of initiatives from below and from above was described as the “bibingka strategy.” That is how our native rice cakes are cooked, with fire from below and from above.

In 1998, I had a brief experience of democratization and development “from above” when I accepted my appointment as Director-General of TESDA, the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority. I managed to broaden its orientation from a narrow singular focus on “globally-competitive” urban-industrial skills development to a more inclusive skills development for rural development and social inclusion. In line with this, I promoted community-based training, through partnerships with NGOs and local governments.

After serving in government with TESDA, I resumed work mainly with NGOs or CSOs (civil society organizations), in my priority fields of community organizing, popular education, and community leadership formation.

But I also agreed to do consultancy work with the National Electrification Administration for the capacity-building of the 119 rural electric cooperatives. I did similar work with the Department of Agriculture for promoting organic agriculture through partnerships among farmers’ organizations, social enterprises and local governments.

Since 2000, I was elected to head a national civil society advocacy coalition on Education for All. We engaged the public education agencies toward our shared goal of an inclusive quality education for all, especially for those who are marginalized, excluded and vulnerable. Our special focus is on alternative learning systems for out-of-school youth and adults.

Last year, I was elected as the president of PRRM, the Philippine Rural Reconstruction Movement, a pioneer NGO established 70 years ago (1952). Our mission is to promote rural development, through building sustainable communities in the upland, lowland and coastal areas, and by working with alliances to influence policies at the local, national, and global levels.

PC: What is your vision for environmental and human rights promotion, advocacy, and education? If you were speaking with future generations of people, what will you be telling them?

ET: By next year I will be 80 years old! I ask myself what have I learned that is worth sharing to the younger generations, including my children and their children.

In the spirit of Freire, I do not have prescriptions, only contributions to the dialogue and conversations that we need to have, as we face a world and a future that is aptly described as increasingly VUCA – volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.

I continue to believe in the vision expressed at the World Social Forum that “Another world is possible” and its later version “A better world is possible.”

How can we hold on to this faith, despite our experience of many setbacks, twists and turns, and frustratingly slow progress toward the goals of our advocacies?

“Patient impatience”

We have to cultivate “patient impatience.” This is one lesson I learned from my years in prison during the long struggle against authoritarianism.

The noun is “impatience.” That is a virtue of the young. But even those who are not so young need to feel the passion for urgent change. The adjective “patient” tempers it, not to dampen the passion, but to provide a perspective that disciplines our expectations.

Compared to 50 years ago, there is greater awareness of the interconnection of human rights, social justice, environment, and climate change. Facing the combined challenges can be overwhelming. All the more reason to find ways of tempering our sense of urgency and expectations.

Those like myself whose original focus is on social justice and human rights, appreciate the perspective provided in the theme of the 2002 Johannesburg Memo – “Fairness in a fragile world.”

“Holding our torches”

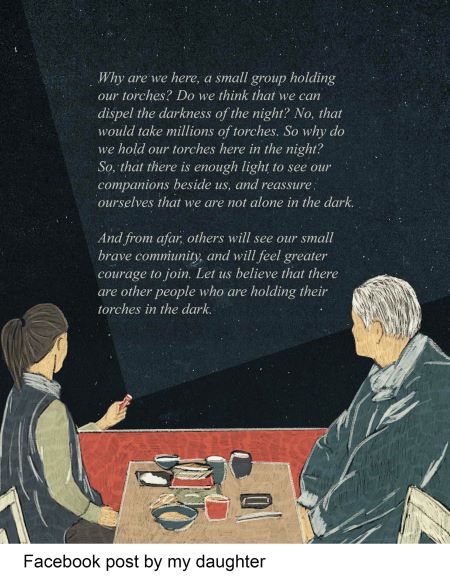

My daughter identifies with the millennial generation, and she has her own passions and life purpose. In one of our conversations, I told her this story from my youth activism, when I was her age.

It was in 1969, and I was part of a 50-day marathon picket that pressed for government action on land issues. When the national elections drew near, we decided to end the picket. We were thankful that some cases were acted upon, but also painfully aware that many more cases were unresolved. To end in high spirits, we borrowed torches from a nearby electoral campaign rally. We marched as we sang songs of our struggle. Towards the end, I was asked to speak. As I looked at the 200 torches against the dark night sky, I felt it was not a time for easy rousing words.

I can’t recall exactly what I said. My daughter posted this summary of what I told her on Facebook, a collaborative poster by her – Ayen dela Torre and her artist friend Rachel Halili:

After the May 2022 elections reported the victory of Ferdinand Marcos Jr, she reposted it on Facebook with the comment, “Remembering my father’s words today during this dark period in our history.”

We should continue to take a long view of our struggles for a better world.

But there are more possibilities for the younger generations to accelerate the pace through collaborative and creative use of the world wide web. It is itself an “arena of struggle” of course and has been used for disinformation and distraction. But I trust that from every generation, new social activists will emerge to find new and appropriate ways to continue the struggle.

Note: Photos from the interviewee’s album.

About Perfecto Caparas:

Writes regularly for Pressenza. He served as a journalist of The Manila Times, Ang Pahayagang Malaya, The Philippine Post, Pinoy Gazette, UCANews, and ISYU Newsmagazine. He is a licensed attorney and lifetime member of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines.

Writes regularly for Pressenza. He served as a journalist of The Manila Times, Ang Pahayagang Malaya, The Philippine Post, Pinoy Gazette, UCANews, and ISYU Newsmagazine. He is a licensed attorney and lifetime member of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines.