We transmit to you the study “Some clues for nonviolence” carried out by Philippe Moal, in the form of 12 chapters. The general table of contents is as follows:

1- Where are we going?

2- The difficult transition from violence to nonviolence.

3- Prejudices which perpetuate violence.

4- Is there more or less violence than yesterday?

5- Spirals of violence

6- Disconnection, flight and hyper-connection (a) Disconnection.

7- Disconnection, flight and hyper-connection (b- Flight).

8- Disconnection, flight and hyper-connection (c- hyper-connection).

9- The different ways of rejecting violence.

10- The decisive role of consciousness.

11- Transformation or immobilisation.

12- Integrating and overcoming duality and Conclusion.

In the essay dated September 2021, the author expresses his thanks: : Thanks to their accurate vision of the subject, Martine Sicard, Jean-Luc Guérard, Maria del Carmen Gómez Moreno and Alicia Barrachina have given me precious help in the realisation of this work, both in the precision of terms and ideas, and I thank them warmly.

Here is the eighth chapter:

Disconnection, escape and hyper-connection

c- Hyper-connection

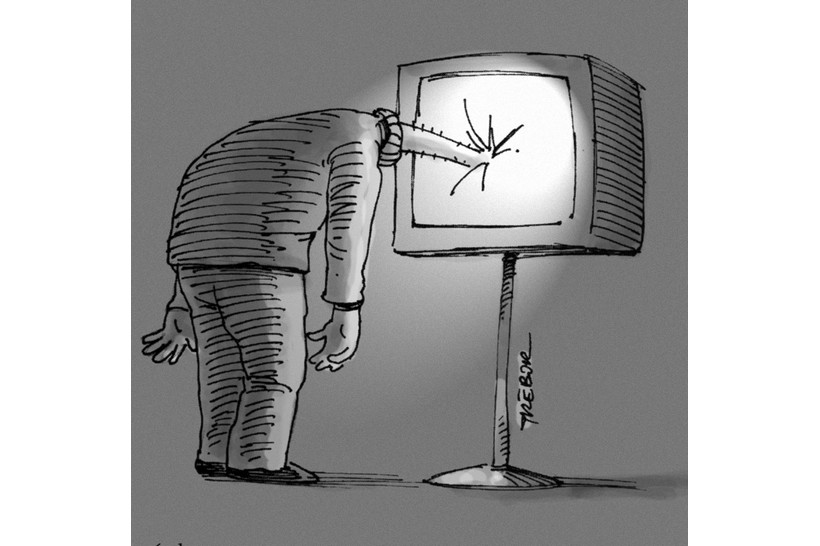

In contrast to disconnection, I can be very connected to violence, perhaps even too connected, to the point of being fully identified with it, glued to it, penetrated by it. I can even become pure violence. In this state, which I register through my visual, tactile and other images, but especially through my kinesthetic images, I find it difficult to be in touch with myself except through my tensions, which are at the surface.

At best, this state makes me irritable, annoyed, touchy, impatient, etc., but it can also upset me to the point of violence.

When I am faced with danger, I become absorbed in the danger. I connect with it and gradually the danger is in me, for me; my whole consciousness is then in danger. If someone tries to distract me and divert my attention, I don’t listen to them, I am obsessed by the danger. The first and most natural reaction is to run away from the danger, to run away from myself in danger and to find images that propel me out of myself, out of the danger that is now in me. This instinctive reaction of defence or escape is identical when I observe violence – I try not to see it any more -, when I receive it – I try to avoid it – or when I inflict it on a person or persons – I expel my inner violence out of myself.

Identification is probably one of the main origins of hyper-connection. Let’s look at a fairly common manifestation, which is anger. The expression being out of one’s mind sums up this state well. The damage caused by an occasional temper tantrum can be easily repaired, but chronic repetition of angry outbursts can become a serious problem, because at any moment one can explode, often over a small thing, and this creates a latent climate of violence for oneself and for those around one. Anger is often triggered when one is upset or disturbed in what one is doing, when things are not going as one wishes, or when one is mentally preoccupied with an unresolved personal problem. The intrusion of the other is irritating me and creating tensions that I have to release; to do so, I focus on the immediate environment – I go looking for culprits. But, in reality, it is because I was identified with the situation I was in – before I was disturbed – that I became tense and discharged my tensions on the object that disturbed me instead of seeing and recognising the source of the problem: my identification. “I am concentrating on a job, or immersed in a telephone conversation, or absorbed in my thoughts…, someone close to me calls me at that moment in an inappropriate way…, it is not the right moment and I point it out to him; but he insists, I feel my tensions invade me…, my response risks being disproportionate, even violent”.

The same phenomenon occurs when I identify with a religious belief, for example, or with a community affiliation. Anything that challenges, demeans or opposes it irritates me and causes me violence. It is because I am identified with my belief or affiliation that words are violent to me. My identification is the root of my violence. I find it very difficult to distance myself and disconnect from the situation, because when my belief or belonging is questioned, it is me who is being questioned, because I myself am the belief, I myself am that to which I belong. In a way, I am both the act and the object of violence.

As a result, I feel attacked and can easily go into a state of anger and even fall into hatred and resentment. I will then give the other person the violent response they deserve, either verbally or physically, if I do not control myself. If I cannot respond immediately, I will wait for the right moment to retaliate and enter an endless cycle.

When I have aggressive feelings and images because someone questions a belief I identify with, I wonder if it is because deep down, I doubt that belief. It seems to me that when I am at peace with my beliefs, criticism of them does not affect me, but rather reinforces them.

When I am not able to distance myself and cannot reason, when I am identified and therefore overly connected to a situation, in order to avoid a chain of events and outbursts that can lead to violent consequences, I have to produce an almost mechanical act to get out of the identification with the situation: I have to disconnect or, graphically, I have to unplug, I have to disengage, before things go too far.

Any situation that normally stresses me out is an opportunity to engrave a new attitude in me. Only in situation can I learn to disengage, to release my tensions, to change my image, to decide to give a moment to the other, to get out of my own object of alienation, to resist the violence that may arise. Only in a situation can I develop this capacity to anticipate my reaction, to be attentive to myself and to give new and unusual responses. My experience has taught me to start by trying to overcome small tantrums, uncompromising situations; then, little by little, to review the deeper reasons for my violence, i.e., my identifications and my registers of possession.

In short, I understand the value of reviewing my own identification systems, as they are the germ of violence, and I understand the value of learning to break the excessive connection with violence when I am trapped by it, which will be discussed in the chapter Transformation or immobilisation.

Finally, I believe that, in education, from early childhood, while teaching the values of belonging to a belief, a group, a club, a country, etc., one should at the same time be warned of the risks linked to identification, including that of becoming violent, and educated to learn to record a centre of gravity within oneself and not outside.