An editorial in the Conservative Party’s El Diario Ilustrado, signed by Joaquín Díaz Garcés and published on Wednesday 12 May 1920, stated: “Arturo Alessandri… is ambitious and audacious. By his race he is a Renaissance Italian. By his mental structure, he is a South American-style caudillo… He will not be satisfied with the moral defeat of the political system… if he becomes President of the Republic, goodbye institutions! He will sweep them away… and the regime from which we emerged in 1830, that of (Manuel) Estrada Cabrera, that of Pancho Villa, that of that class of political adventurers who have been obstinate in saving the countries of this unfortunate container, but leaving them in such a state that it is not possible to save them a second time, will begin too late for us”.

Alessandri Palma was a member of the Liberal Party and in 1920 he presented his presidential candidacy on behalf of the Liberal Alliance, a coalition made up of a sector of the Liberals and moderate progressive political forces such as the Radical Party and the Democratic Party, the latter heavily influenced by the forward-looking ideas of Francisco Bilbao and in which until 1912 Luis Emilio Recabarren, later founder of the Communist Party, had been a member. His competitor was Luis Barros Borgoño of the National Union, whose main forces were the Conservative Party, the most right-wing sector of the Liberal Party and the Nationalist Party, of little electoral weight and ephemeral existence, but for a long period the undisputed historical reference point of the radical right.

The case of Pedro Aguirre Cerda, the Popular Front candidate, referred to a text that was also published by El Diario Ilustrado on 8 October 1938, signed by Senator Ladislao Errázuriz, which stated: “The triumph of the Popular Front is synonymous with immediate social revolution and can only end in bloody tyranny. The bourgeois parties which accompany the Marxists are only the first victim of their parasitic and corrosive action, the screen behind which they prepare the absorption of power and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat (…) The men who hide, as in every revolution, the overwhelming advance of the devouring pack, use here – as elsewhere – their mellifluous and insinuating oratory to reassure their fellow citizens. Do we not know that the next acolytes of the Front candidate, his most prominent lieutenants, have already spoken, in squares and theatres, that the knives must be used to cut the throats of the capitalists and the ropes that are being twisted to hang the bourgeoisie?

The Popular Front was a progressive coalition composed of the Radical, Socialist, Communist and Democratic parties, which in 1938 presented the presidential candidacy of Pedro Aguirre Cerda, a moderate radical. During the Popular Front’s presidential term, of course, there was no communist dictatorship, public education was encouraged, technical and industrial education was promoted, programmes and public policies were developed to combat poverty and strengthen public health, and the Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (Corfo) was created to promote the industrialisation of the country, which was strongly resisted by the right wing in the Senate.

According to historian Rafael Sagredo:

Campaigns of 1958 and 1964

A new stage in the evolution of the terror campaigns, now with a much more sophisticated discourse, and with the variants of the time, came about as a result of the 1958 presidential elections, which pitted Salvador Allende against Jorge Alessandri and, especially, in the 1964 presidential campaign, in the midst of an international context that was impossible to ignore, such as the Cold War, and in which Eduardo Frei Montalva and Salvador Allende competed.

The media played a decisive role in both elections, with intense campaigning in newspapers and on the radio. Another unprecedented element was the external financing of political campaigns and the use of television as an element of propaganda.

An example of the content and characteristics of the 1964 terror campaign is the use of images: Fidel Castro was shown giving instructions to Luis Corvalán, one of the leaders of the Communist Party of Chile and a member of the Popular Action Front coalition that supported Salvador Allende; the press, as well as the caricature, showed Fidel Castro as a central and therefore decisive element in Allende’s campaign and in what Chile would become in the future if the left-wing candidate triumphed.

The international dimension, the Cold War, was used to encourage and stimulate the anti-communist sensibility that the terror campaign transferred to society as fear of communism represented by Allende.

A sharp contrast between “good” and “evil” was promoted, as a result of which the 1964 election was presented as a true plebiscite between freedom and tyranny; democracy and totalitarianism; political guarantees (Frei) vs. oppression (Allende); progress vs. decadence; property, capitalism and market society vs. confiscation, vexation and a host of other calamities.

The campaign of terror, that of Frei and the right wing that then supported him, manifested itself as a national crusade, for Chile, versus the candidate of the left who obeyed the dictates of international communism; who was selling out or surrendering definitively to Cuba, China and the Soviet Union.

The Cold War played a decisive role; it was a question of saving Chile from the communist danger. Images of executions were shown in the press, asking Chileans: “Is the wall the future you want for your father, your brother, your friend?”, accompanied by a very dramatic, almost epic message: “22 days to go!

In this way an image was built up that was intended to provoke fear of Allende and what he supposedly stood for. Using international funds provided by US agencies, anti-communist sensibilities were activated, creating an emotional reaction of fear through the press and radio, and a discourse was articulated in which the representations heightened the fear of mass society, another fundamental element in the 1960s, and which involved the use of persuasion techniques. Stereotypes associated with communism were exploited and disseminated, images that generated a social effect of terror. Accompanied or reinforced by dramatic questions, categorical judgements and drastic choices.

The plebiscites during the civil-military dictatorship

New versions of the campaign of terror, now taking advantage of mass media such as television, which had expanded its coverage, were developed during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet for the consultations of January 1978, 1980 and, in all its magnitude, as a result of the 1988 YES and NO plebiscite.

For the 1988 plebiscite, symptomatically, the only possible options were YES and NO, with all the meaning that these words have for ordinary people. For the forces that supported the YES vote and, therefore, Pinochet, the NO vote represented chaos, anarchy, a return to an era they all repudiated, which was none other than the country’s democratic past associated with the Marxist regime of the Unidad Popular.

In the months leading up to the plebiscite of 5 October 1988, numerous pamphlets circulated in Santiago and other cities showing how the opposition to Pinochet was represented. In one of these, the leader of the democratic forces for the NO, Ricardo Lagos, appears alongside the communist Luis Corvalán and the “very incarnation of evil” at the time, the socialist Carlos Altamirano: “The Marxists control the NO. Socialists, Communists, Miristas, Rodriguistas. The old and sinister Popular Unity. Do you think this is good company?”

These are phrases, images and representations aimed at the centrist electorate and intended to provoke unease, real fear with regard to the political, democratic, forces that supported the NO option. An attempt to demonise the Concertación Democrática by making it appear not very “democratic” and not at all “trustworthy”. Hence the appeal to citizens: “Think about it and make up your mind”, “it is still time” to opt for the YES.

Propagandistic announcements in which the NO option is represented as chaos, queues, disorder, demagogy, inflation, statism, takeovers, interventions and unemployment, all, moreover, equivalent to a bomb. While the YES alternative through green hope and order, both in the face of a family that must make its decision, were devised and disseminated through the press by the YES supporters. As well as through pamphlets offering a brutal contrast between the two positions.

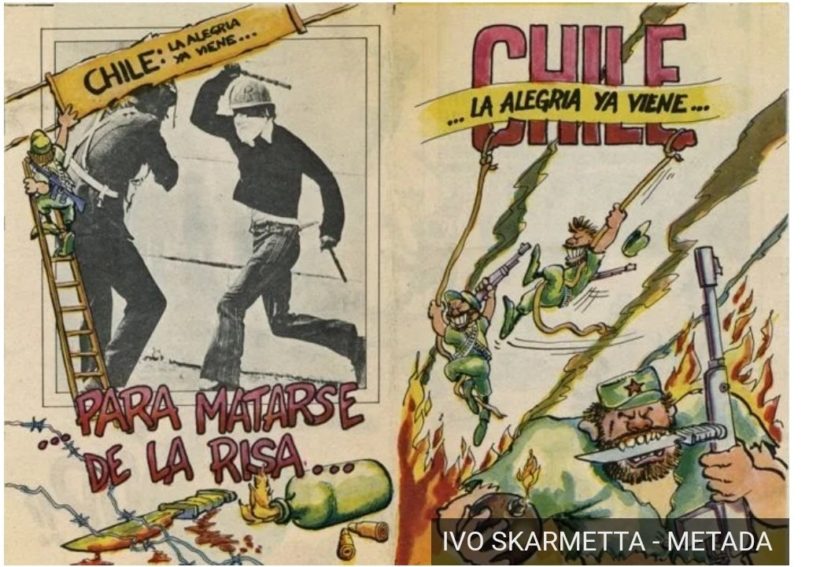

In another representation of the NO option, supporters of the Pinochet regime showed their opponents, the Concertación Democrática, associated with violence, deforming their slogan, “La alegría ya viene” (“Joy is coming”) by using a bomb and alluding to the Popular Unity government, in an attempt, which ultimately proved futile, to discredit that position.

And how did Pinochet’s opponents react to a campaign that had been going on for years? Through the hope represented by a rainbow, with an optimistic campaign slogan such as “joy is coming”, and humour as a strategy to confront fear and counteract the campaign of official terror.

The NO offered the rainbow, and a refreshing and positive vision of the future in case citizens opted for the Concertación, using sarcasm, irony and humour to undermine the image of a Pinochet who offered little guarantee of respecting the will of the people. That is why he was shown, as one of Guillo’s cartoons did, in a witty and witty way, stating: “if we don’t sweep away, we sweep away”.

History shows that fear as an instrument of the Chilean political struggle is essentially associated with the fear of the right, with its desperation in the face of a future that it sees as inevitable, and also with a reaction motivated by its own anguish at change and the loss of power, in which sectors of the middle class also participate, and in the face of what is perceived as a threat, an internal enemy has been created and a critical scenario of society not opting for its criteria, positions and electoral preferences. This is a prediction that, time and again, the experiences of the last decades and in the face of the most diverse issues, have shown to have failed.

On the other hand, for the 2009 presidential campaign, which gave victory to Sebastián Piñera for the first time, a powerful alliance between conservative sectors, functional NGOs and the red chronicle of the television channels, one of them unusually owned by Piñera himself, inoculated the population with fear of crime, despite the fact that, for example, Santiago was, according to hard data, one of the least dangerous large cities in Latin America. It was the time of Bombo Fica’s joke in which he said that his grandmother, who lived in the countryside and watched television so much, was terrified of being burgled, with the detail that she had no car and no gate. It was also the time when the then candidate Piñera took over the media and road signs with an eloquent phrase: “Delinquents, your party is over”. It was not the only factor, but fear favoured the one who ended up winning the election.

For the 2017 elections, another powerful alliance between conservative political sectors, some from Chile Vamos and others from the New Majority, plus again the television channels, proposed that if Alejandro Guillier won, Chile would begin a process of deterioration until it became Venezuela. That is when the word Chilezuela was coined, which caused fear among the citizenry.

Now, the electoral campaign of the last presidential elections in Chile was also a trail of fake news and hate campaigns against Boric, articulated and financed to a large extent by Atlas Network foundations operating in Chile, among them Nueva Mente, Fundación para el Progreso (FPP), Libertad y Desarrollo and Ideas Republicanas, defenders of Pinochettism, which are very present in the media and networks through youtubers and bots.

The ultra-conservative Kast triumphed in the first round, despite the social outcry and his call for structural changes. Kast is an advocate of the refusal to change the Constitution forged during the dictatorship, as during his university days he was the youth spokesman for the Yes campaign for Pinochet in 1988. The former candidate is a practising Catholic within the German Schönstatt movement, he also has links with the ultra-Catholic organisation Hazte Oír, and with the party sponsored by Vox through the Madrid Charter, which articulates an international network with other signatories such as Javier Milei (Argentina), Bolsonaro (Brazil), Arturo Murillo (minister of the Bolivian coup government of JeanineÁñez, arrested in the USA for bribery and money laundering in the Bolivian coup of JeanineÁñez, arrested in the USA for bribery and money laundering in the Bolivian coup. Fernando Donoso (former defence minister of Ecuador under Guillermo Lasso), Jorge Montoya (retired Peruvian military officer who supported Fujimori’s coup and threatened a military coup if the electoral fraud in the last elections was not recognised), María Fernanda Cabal (Uribista linked to drug trafficking and Colombian paramilitary groups, defender of Colonel Mejía, convicted of dozens of false positive murders of civilians), Alejandro Chafuen (director of Atlas Network for 17 years) and a long etcetera.

On the other hand, Gabriel Boric was falsely accused by Kast and his followers of being a drug addict, animal abuser, street terrorist, financed by Hamas and Hezbollah, supermarket thief, linked to drug trafficking, etc.

The network of foundations involved with Atlas Network is financed by some of the biggest fortunes and companies in the United States, such as the Koch family, Exxon or Philip Morris, with the aim of intervening in the democracies of third countries. It was created during the Reagan administration and defends the principles of free trade and the theories developed by Milton Friedman of reducing the state to a minimum, privatisation of all services and the opening of foreign capital to exploit state resources, which were applied in Operation Condor, with the participation of the CIA and the US government, with the creation of the so-called Schools of the Americas, which the United States set up in the Panama Canal Zone and other military districts located in the south of the US territory. All these military personnel were trained in techniques of torture and repression against the population under the doctrine of national security and the fight against communist subversion. Once installed as de facto rulers, they kidnapped, tortured and murdered hundreds of thousands of civilians. Among the 83. Among the 83,000 students who passed through their classrooms were Augusto Pinochet himself, the Argentinians Rafael Videla, Leopoldo Galtieri and Roberto Viola, the Bolivian Hugo Bánzer, the Salvadoran Roberto D’Aubuisson, the Panamanian Manuel Noriega, the Guatemalan Efraín Ríos Montt, Venezuelan Efraín Vásquez and Ramírez Poveda, Honduran Romeo Vásquez and Luis Javier Prince Suazo, Colombian Jaime Lasprilla, Peruvian Vladimiro Montesinos, Paraguayan Stroessner, Uruguayan Seineldin and Nicaraguan Anastasio Somoza.

One of the foundations with the greatest impact outside Chile is the Fundación Para el Progreso, directed by Axel Kaiser, brother of Johannes Kaiser, Leif (creator of the Chilean Rifle Association) and Vanessa, a Republican Party councillor and director of the Centre for Libertarian Studies.

Sergio Melnick, Pinochet’s minister, is very active on social networks and in the media, and is often the first to launch the lie and insult of the day.

Teresa Marinovic, for her part, came to the fore when the 16-year-old boy thrown by a carabinero off the bridge into the Mapocho River was left in a coma, asking how the boy who was swimming in the river was doing.

Marinovic and Melnick, along with Kast, campaigned with the HT #RechazoTuTongo, saying that the young man had jumped in alone.

Surely the most ultra foundation is Ciudadano Austral. Not only does it widely disseminate content from Vox, Fundación Disenso or La Gaceta, but it has also edited the book La Nueva Derecha, together with Vanessa Kaiser’s Centro de Estudios Libertarios, with a preface by Agustín Laje and Alejandro Chafuen and reviews by Abascal. Most strikingly, it organises talks on Pinochet by Mauricio Schiappacasse, author of the titles Augusto Pinochet: el reconstructor de Chile (Augusto Pinochet: the rebuilder of Chile) and Augusto Pinochet, un soldado de la paz (Augusto Pinochet, a soldier of peace).

The use of fear has been a strategy that the right wing and the power groups have employed for generations to keep the masses in a passive state so that they do not become autonomous and endowed with critical thinking. They do this under the belief that ordinary people are ignorant and naïve, taking into consideration what the Nazi regime’s Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, said: “A lie a thousand times repeated, will become the truth”. The new institutionality and democracy protected by the founder of the UDI, Jaime Guzmán, is a clear example of this. However, the right and the big power groups forget that times have changed and that the massification and sophistication of technology and social networks have broken down all kinds of barriers to the circulation of information. This has also contributed to the fact that people are no longer as naïve as before, and have become increasingly empowered in their process of awareness-raising in order to acquire autonomy, demand rights and reaffirm their duties within society. It is to be hoped that citizens have learned their lesson and will not fall into the clutches of the terror campaign in the run-up to the constitutional plebiscite on 4 September.