Out on the Town

Magnus Hirschfeld and Berlin’s Third Sex

Years before the Weimar Republic’s well-chronicled freedoms, the 1904 non-fiction study Berlin’s Third Sex depicted an astonishingly diverse subculture of sexual outlaws in the German capital. James J. Conway introduces a foundational text of queer identity that finds Magnus Hirschfeld — the “Einstein of Sex” — deploying both sentiment and science to move hearts and minds among a broad readership.

______________________________________________________________________________

by James Conway

By the time Magnus Hirschfeld died in exile on May 14, 1935 — his sixty-seventh birthday — the German sexologist had already witnessed his own annihilation at least twice over. Presumed dead after a brutal attack by far-right thugs in early Weimar-era Munich, he got to read his own obituary in the newspaper while convalescing. And years later, shortly after the Nazi takeover of Germany, an exiled Hirschfeld viewed a newsreel of the first major book burning, which showed the SA not only casting decades of his research onto the pyre, but a bust of Hirschfeld himself.

Magnus Hirschfeld was born to a Jewish family in the Prussian spa town of Kolberg in 1868, but the man whose investigation of difference so incensed his countrymen came forth on a later birthday — May 14, 1897 — when Hirschfeld formed the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee at his medical practice in Berlin. Arising out of culturally conservative Wilhelmine Germany, this Committee was the world’s first gay activist group, from which Hirschfeld later emerged as one of history’s most important figures in the study of gender and sexuality.

Pages from the 1899 Yearbook for Sexual Intermediaries (Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen) listing donors to the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, aimed at homosexual liberation (Befreiung der Homosexuellen). Several donors use the pseudonym Dorian Gray (“Dorian Gray in Vienna”, “Dorian Gray from Monte Carlo”) in light of the recent criminal trial of Oscar Wilde. Source.

Hirschfeld fought all his life to have Paragraph 175 struck off. It not only shadowed his own existence as a gay man; through his practice the doctor also saw its devastating impact on men who lived in fear and shame, prey to blackmailers. Who else, after all, would report a consensual sex act to the authorities? But as those names on the petition indicate, there was more support for abolition than one might expect. In 1898, August Bebel, head of Germany’s Social Democrats, became the first politician to speak out in favour of gay law reform; particularly striking was his insistence that gay men were to be found in large numbers at every social level.

No one knew this better than Hirschfeld himself, the antithesis of the cloistered academic. He went out into society, actively participated in the lives of the people he was writing about — not just gay men but a full spectrum of lesbians, bisexuals, trans men and women, cross-dressers of all persuasions — then went back, analysed, formulated, and reappeared before the public with his findings. Hirschfeld’s friend, writer Else Lasker-Schüler, referred to him as a “father confessor”, but his transgression in the eyes of credentialed colleagues and the conservative mainstream was to have breached the sanctity of the confessional, or the academy in this instance.

Photograph of Magnus Hirschfeld seated between Bernard Schapiro, the Institute for Sexual Research’s Assistant Director, left, and medical student Li Shiu Tong. Karl Giese and Hirschfeld’s life partnership expanded to include Li after they met during the doctor’s Chinese lecture tour, dating the photograph after 1931. Source

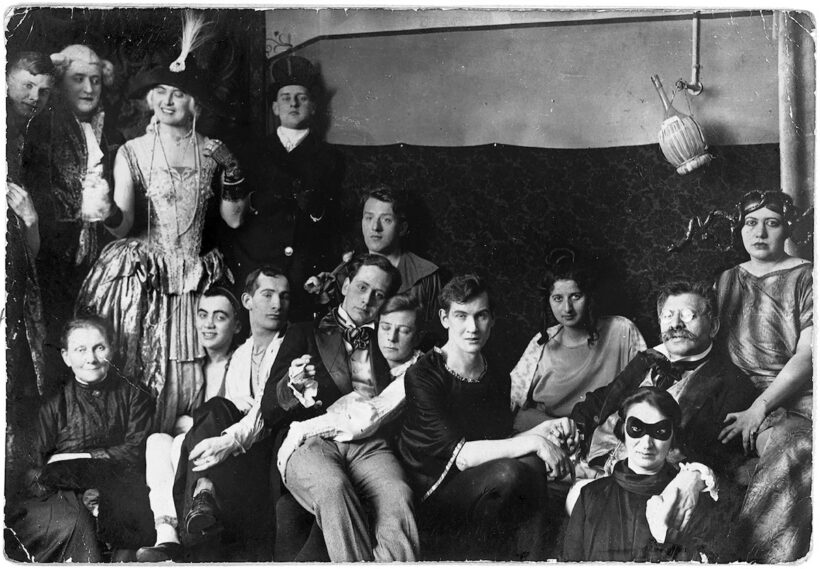

Hirschfeld’s laboratory was queer Berlin — its beats, balls, and bars. Unique among German urban centres, the capital entered the twentieth century as a metropolis. It had experienced phenomenal growth, multiplying twentyfold in a century; in global comparison, only London, New York, and Paris were larger. To both settled Berliners and newcomers the city offered not just material opportunity, but the promise of transformation, or revelation — the prospect of sympathetic company in which to bare one’s true self. It had supported a gay underground since at least the time of Frederick the Great, when Austrian author Johann Friedel indignantly reported on the city’s male brothels in his 1782 Briefe über die Galanterien von Berlin (Letters on the Libertinage of Berlin). In Hirschfeld’s day, the chief of Berlin’s police, Leopold von Meerscheidt-Hüllessem, eschewed open confrontation with the city’s sizeable sexual minority and instead maintained a policy of containment and observation — a key factor in the development of a confident, diverse subculture.

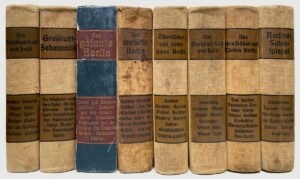

But Berlin’s rapid expansion had rendered the city a stranger to itself. Hans Ostwald, an ambitious writer a few years younger than Hirschfeld, sought to chart the furthest reaches of the modern city, and the result was one of the most expansive accounts of urban experience ever undertaken — the Großstadt-Dokumente (Metropolis Documents). Beginning in 1904 with Ostwald’s own Dunkle Winkel in Berlin (Dark Corners in Berlin), a study of vagrants, and ending four years later with the shiny nouveau riche revels of Edmund Edel’s Neu-Berlin, the fifty-one editions fed the voracious curiosity of the Bildungsbürgertum — the educated middle class. Viewed together, the Metropolis Documents resemble a compendious study of a distant colony, especially in the row of imposing cloth-bound thematic convolutes which collated five volumes each. But it was the alien customs of modern, urban life that the Metropolis Documents mapped, with a particular focus on the disadvantaged and marginalised — prostitutes, bohemians, single mothers, gamblers, spiritualists, alcoholics, and criminals — as well as civil servants, teachers, seamstresses, musicians, actors, athletes, and bankers. Three quarters of the titles were about Berlin (with brief digressions to Hamburg, Vienna, and St Petersburg). And when Ostwald sought to depict the lives of sexual outlaws in the German capital, he turned to Magnus Hirschfeld.

James J. Conway’s personal collection of the Metropolis Documents. Berlin’s Third Sex is included in the volume titled Das erotische Berlin.

The resulting 1904 volume was by some distance the most successful of the Metropolis Documents. Today, few works emerge from the archives with the urgency of Hirschfeld’s Berlins Drittes Geschlecht (Berlin’s Third Sex). To be fair, it didn’t exactly come out of nowhere; it wasn’t even the first Hirschfeld text to address the “third sex” — at the dawn of the new century he had issued a pamphlet for a broad readership entitled “What People Should Know about the Third Sex”. The “third sex” was a label of convenience at a time when Hirschfeld’s studies were still blurring distinctions between gender and sexuality, conflating them with physiological characteristics. In his research into sexual attraction he would soon settle on the notion of a continuum — decades before Alfred Kinsey — noting that to be positioned at either extreme, heterosexual or homosexual, was the exception rather than the rule. Hirschfeld was hardly alone: a large number of German works at the time examined this “third sex”, in fiction and non-fiction, but with little consensus on what the category actually encompassed: lesbians and gay men? Trans men and women? Emancipated women, perhaps? Hirschfeld’s preferred label for gay and trans individuals — a distinction not always clear at the time — was “Urning” (uranian), but he evidently adopted the more modish term “third sex” to lure as broad a readership as possible.

(To be continued…)

James J. Conway was born in Sydney and now lives in Berlin where he is a translator from German to English, both commercial and literary. In the latter capacity he has translated and published eight books for Rixdorf Editions, most recently Three Prose Works by Else Lasker-Schüler. He has written for publications such as the Times Literary Supplement and the Los Angeles Review of Books, as well as his own repository of alternative cultural history, Strange Flowers.

____________________________________________________________________________

This article was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/