Reports included conditions from skin diseases, anxiety, and depression to the loss of the will to live. Who are these women victims of mining, and how has the activity altered their ways of life and existence?

By Jacqueline Melo e Michele Marinho

“When a crime of this magnitude happens, there is no other group more affected, with such dramatic dimensions, than women,” points out Leila Regina da Silva, analyst of the Socioeconomics and Culture management of the Núcleo de Assessoria às Comunidades Atingidas por Barragens (Nacab), based in the municipality of Viçosa and active in several cities in Minas Gerais.

The state of Minas Gerais has suffered in recent years from two large-scale criminal disasters: the rupture of the Fundão dam in Mariana (2015), which was the largest environmental disaster in Brazil, and the rupture of the Córrego do Feijão dam in Brumadinho (2019), considered the one with the greatest social impact in the country’s history. The damage from these environmental crimes still affects the lives of thousands of women, even those who live miles away from where the mud reached.

Although mining accounts for about 8% of the state’s GDP, with revenues in the billions – in 2021, Vale alone had record profits of R$ 121 billion (around U$ 22 billion) – the effects of mining activities in those territories cause massive changes in the way of life and livelihoods of the communities as a whole, but with more serious damage to the women affected.

This is the case of 42-year-old saleswoman Fernanda, a former employee of Shopping da Minhoca, a commercial area for fishing items on the sides of the BR-040 highway, in the municipality of Caetanópolis, Minas Gerais. She says that since February 2019, after the Brumadinho disaster, fishing has been prohibited in the river. With the lack of customers at the site, Fernanda, as well as other employees, were fired.

Fernanda Soares, a former saleswoman of Shopping da Minhoca, in Caetanópolis/MG – Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

“Nowadays, I arrive at home very disturbed because I also take several types of medicine, antidepressants for panic disorders, to control anxiety. In fact, during this period, I easily gained about 25, 30 kilos. It’s a matter of great anxiety, I have already felt sick, I have gone without food and yet gained weight due to my degree of anxiety,” says Fernanda Soares.

“At a moment’s notice, they [the fishers] started to vanish because there was no more meaning in going to relax by the riverbank that you no longer had access to it. […] What kind of joy would you have to go to a riverbank, in which you used to see the crystal-clear water, to see it totally polluted? That’s a stab in the heart of anyone who is used to that place.”

Fernanda is part of the Shopping da Minhoca Affected People’s Committee and says that receiving the first installments of Vale’s Income Transfer Program (PTR, in Portuguese), in April this year, was the result of much struggle and recognition of the workers as “traditional peoples and communities”. The Paraopeba River is more than a kilometer from this commercial region, and therefore the community was not recognized as affected.

“Despite what many people think, it’s not because we weren’t literally hit by the mud that we weren’t affected, but our dignity was affected because the Shopping da Minhoca was a self-sustaining community. We were hit at this point, from the moment that many people got into debt and are still doing so today.”

“Marilei’s booth” at the Shopping da Minhoca, Caetanópolis/MG – Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

“We weren’t damaged by the mud from the outside, sit down and talk to each person in that little corner, and you will see. The mud from the outside means nothing, but on the other hand, on the inside, the mud has taken over,” says the saleswoman.

Who are the women affected?

“We are talking about women who are black, young. We talk about layers of vulnerability, of violation. It’s important to look at each of them in this place. Because even when we talk about women, we don’t do so homogeneously. We talk about these diversities, these facets. One thing is to talk about a white woman, but another thing is to talk about a black woman,” explains Leila Regina da Silva, Socioeconomic and Culture Manager Analyst of the Nacab.

Between June and August 2021, a particular survey was conducted for the first time to understand the damage caused to women. The “Bulletin Mobilization: being a woman affected,” was made by the Independent Technical Advisory Services (ATI, in Portuguese) of the Nacab.

According to Leila Regina, although families are devastated, it is the women who suffer the most because “they start to bear a much greater pressure, within the dimension of care, which is socially assigned to the woman. Men and children are more present inside the house, doubling the demand for women’s work if it is she who takes care of the house. There are more hours spent on tidying and cleaning, in this process of getting sick.”

In the same survey, 1,084 people were interviewed, residents of the so-called region 3.

Municipalities of the Paraopeba River Basin Region 3 – Source: NACAB

The bulletin points out that, of the total number of people affected, 47.8% are women, 57.3% declare themselves black, 47.8% are of adult and productive age (between 30 and 59 years old) and have low education levels, with 34.8% have not completed elementary school education.

Regarding income and autonomy, the report shows a 20.2% indebtedness of women in Region 3, besides the significant increase in basic expenses such as health (44.2%), transportation (37.5%), and food (58.2%).

About a quarter of these women lost their jobs (22.8%), while most of them had a decrease in their income (52.2%), thus becoming dependent on Vale’s emergency payment. Most of them are not served by public policies or social programs (74.4%).

Almost half of these women (45.7%) had direct contact with dust and mud, increasing their workload in cleaning and housekeeping. More than 40% of the women noticed an increase in the flow of strangers in the neighborhood, which caused insecurity and fear of harassment and other forms of violence.

Maria de Lourdes Honorato, hairdresser and chef, resident in Taquaras, MG.- Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

“I take anti-depressant medication, I don’t sleep properly. My store is on the avenue. The trucks go up and down, and there’s that dust that you keep breathing. My breathing is no longer the same… […] Before the Vale dam burst, we had a place, everything was more natural for us. Not today, you walk insecure because you know that you’re feeding on chemical dust”, says Maria Lourdes Honorato.

Born in Belo Horizonte, Maria de Lourdes decided to move to Taquaras, a community in the municipality of Esmeraldas, in the metropolitan area of the capital of Minas Gerais, in search of a better quality of life. She worked as a hairdresser for 28 years and, during the pandemic, she decided to change her line of work: she opened her own restaurant, where she cooks and sells locally produced delicacies.

Since the disaster-crime of Brumadinho, the Paraopeba River, which is less than a kilometer from her house, was contaminated, changing the entire life dynamic of the community, especially that of the women.

“Today, what I see is Taquara’s women inside their home, those who used to be fishers. Today, they live depressed inside their homes, they don’t come to the salon to do their hair anymore, as they did in the past. Occasionally, this is also due to their lack of resources, which used to come from the fish. They’re living on medication, taking it at home. I see that the Taquara’s women are sick because we do have no entertainment at all, we have nothing.”

Maria de Lourdes lives on a small farm, and she reports that the fruits and vegetables she grows are rotting and not ripening anymore. “In the past, I didn’t buy vegetables, they were harvested here. Everything that I ate was clean, there were no chemicals in it at all.”

Maria de Lourdes Honorato holding unripe fruits – Taquaras, MG.- Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

She says that, in January 2022, the flooding that hit the Paraopeba River caused more extensive damage to the community than the Brumadinho burst. “Today, the riverbank is so dangerous. There is a place that was hit the most, where the houses were destroyed, and where the flood passed and caught that rejects with sand, with everything. When you arrive at that place, which is close to my house, your sadness is absolute. There were mansions, beautiful houses, and gardens, and today, there’s nothing left.”

[This is a house and a family destroyed by Vale and the State of Minas Gerais] A protest from a family that had their property affected by the Brumadinho dam burst in Taquaras, MG – Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

The growth of mining and the commodities exportation

In 2020, the area mined in Brazil was six times larger than that reported in 1985, increasing from 31,000 to 206,000 hectares, representing a 600% increase over the past three and a half decades. The data are from the organization MapBiomas, collected by satellite images using artificial intelligence.

MapBiomas Project: mapping the surface of industrial mining and wildcat miners in Brazil. Source: MapBiomas.org

According to the mapping, the state of Minas Gerais occupies second place in the total area mined, covering a total of 33,432 thousand hectares. Iron ore, the main export item of this state, represents 1/4 of the total extracted minerals in Brazil.

The technological advances have pushed up the productivity of iron ore. From January to December 2021, Minas Gerais was responsible for 41% of Brazilian foreign sales of this ore, with a collection of US$15 billion.

The great demand for iron ore has motivated the increase in production and also the expansion of the construction of tailings dams, often built using methods that do not guarantee the safety of the ecosystem.

The MapBiomas study also points out an increase in the activity of wildcat miners, many times carried out clandestinely, using potentially toxic metallic minerals. With the increased flexibility of environmental legislation in the last few years, this kind of mining has moved towards indigenous territories and conservation units.

Traditional Mining Community

There is another type of mining, in the riverbed, artisanal and traditional, very common in regions like the city of Antônio Pereira, in the Ouro Preto district.

Interview at the home of miner Ivone Zacarias, in Antônio Pereira, in the district of Ouro Preto/MG. Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

According to the miner Ivone Pereira Zacarias, the activity is not harmful to the environment, “because we don’t work with machinery, not even use mercury […], because it pollutes the river, destroys nature, the fish, and our health. Mercury is a poison. What really causes damage is the mining company, due to their machinery, the holes, and the dust that destroys the plants.”

Born and raised in Antônio Pereira, Ivone, 52 years old, learned to mine with her parents when she was 11 and taught the same profession to her kids and grandkids, as a livelihood guarantee.

In May, the region’s miners were arrested and had their tools confiscated by a Federal Police operation at the behest of Vale. Since then, they have been unable to work.

“You do not take much gold when mining, you won’t get rich. But you go in the morning, and in the afternoon there’s already a bit of gold to buy a packet of beans, cornmeal, rice, cookies, and milk, that your son asks for sometimes, and you don’t have. And what does Vale want? That everyone in our community becomes an outlaw?”

Ivone Zacarias in her mining area in Antônio Pereira, in the district of Ouro Preto/MG. Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

Ivone says that mining enterprises have been present in the region where she lives for more than 20 years. And she highlights that the municipality has suffered with the “invisible mud,” due to the fear of a rupture of the Doctor Dam, owned by the Vale mining company.

“Why can Vale mine, end up with our ore, our gold, and we, who are from the place, can’t mine? […]. It is not killing us with mud, as it did in Brumadinho, for now, because the dam did not break. But it is killing us with depression, we are all sick here. Old people are taking medicine, children with serious problems, and this itch we have in our bodies, from this dust, from these tailings,” reports the miner.

For Lais Jabace, coordinator of the registration process of those affected by Caritas in Mariana, bed mining is an income supplement or a core income for several families, and it is an activity that has a deep relationship with the environment and the surrounding community. Caritas is an international humanitarian confederation run by the Catholic Church, which promotes solidarity actions for communities affected by socio-environmental disasters or in vulnerable situations.

“The economy that revolves around this kind of mining is local, from the machinery they use to the instruments made, built, and bought there. […] This population buys and consumes in the region, which is entirely different from the mining of a big corporation. Both in terms of materials for the activity and in terms of where the resources go. The profit, the revenue, is not reinvested in the region, even if it has as part of the possible process of tax rebates for social responsibility policies,” says Laís.

Commodity Exports

To the popular lawyer Larissa Vieira, a member of the Margarida Alves Collective of popular consultancies and of the National Network of People’s Lawyers (Renap, in Portuguese), the state of Minas Gerais is currently experiencing an intensification of the mining enterprises due to the choice of a model that is essentially mining and focused on commodities exports.

“Even in the face of the context in which we live, of the failure of this model, with the rupture of two tailing dams, resulting in great losses and damage to this population, we see that the state has not backed down, in terms of trying to find economic alternatives for our state,” she ponders.

Larissa points out that the state environmental legislation has been loosened, even after the rupture of the Fundão dam in 2015. “This is a very aggravating factor, which makes the admission of enterprises easier, often at the cost of violating the rights of communities, of not listening to the population, in relation to what the population considers important, in terms of development models.”

Health and Reproductive Justice

Reproductive Justice is a tool for ensuring the citizenship and rights of women and their communities because it focuses on sexual and reproductive life through the lens of social justice.

The concept of Reproductive Justice was developed in 1994, in the context of the United Nations Conference on Population and Development, which took place in Cairo, and is considered to be a landmark in the international definition of sexual and reproductive rights of women. In effect, Reproductive Justice is a tool for ensuring the citizenship and rights of women and their communities, as it focuses on sexual and reproductive life through the lens of social justice.

Mariana Prandini Assis, a professor at the Federal University of Goiás, explains that “black women have mobilized themselves to denounce the individualistic logic of choice underlying the demand for sexual and reproductive rights was insufficient to respond to the injustices that marked their lives. And as a result, they claimed the right to have children, to not have children, but also the right to raise their children in healthy and sustainable communities, with dignity and respect.”

According to the lawyer Larissa Vieira, the concept of Reproductive Justice “brings the perspective of free bodies, of people free to choose their own destiny, with autonomy, bodily dignity, which in fact will never be achieved in this context of big enterprises. The environmental impact study itself does not think about women. Sometimes it even detects an impact on their lives, but nobody has thought of any alternative solution.”

Territories and Ecosystems: Environmental Reproductive Justice

Reproductive Justice encompasses a broad view of the environment, including some conditions necessary for people to make decisions, including but not limited to adequate wages, access to health care, quality education, housing, and safety.

Access to material and socioeconomic conditions is necessary so that women have dignity over their choices, such as having or not having children, and how to take care of them in sustainable communities.

Therefore, Reproductive Justice can be thought about in a territorialized way, concerning the struggles that happen in the territories. According to Professor Mariana Prandini Assis, in the last few years, the concept of Environmental Reproductive Justice has been gaining strength, steaming from the development of indigenous movements in the Americas, which integrates reproductive justice and social-environmental paradigms.

To the professor, this new way of looking requires “the evaluation of the socio-environmental impacts including also the damage to the processes, subjects, elements, and spaces of life reproduction, that is, the individual and collective bodies, the culture and the social symbols, the sexuality and reproduction, and the individual and communities ability to perform their reproductive liberty with dignity.”

How to live without the river?

In the context of large enterprises, such as mining companies, all ecosystem, including the human and non-human ways of living, is affected.

Leandra Moreira, 25 years old, is a fisher and resident of Retiro dos Moreira, a village with around 200 residents in Fortuna de Minas (MG), which was recognized two years ago as a remaining quilombo community. She reports the environmental and social changes that happened in her territory after the Paraopeba River contamination.

“We had plenty of fishers here, and there was a lot of movement in the community. The fishers came and gave fish to us when we couldn’t go to the river. My house is one of the closest [to the river], so they bought eggs, chicken, and vegetables. They also brought things from the city to us when they came,” says Leandra.

Leandra Moreira, resident of the Retiro dos Moreira quilombo, in Fortuna de Minas/MG – Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

Leandra says that the river degradation led to the loss of an essential space for leisure and sociability in the community. “Entertainment here was heavenly! At the weekends it was known, everyone would be at the river. Be it for fishing, or swimming. Every so often, we would go just to sit by the river and eat some fried manioc flour, or we would catch a fish and eat it on the spot.”

The banks of the Paraopeba River, in Retiro dos Moreira, at Fortuna de Minas/MG.- Photo: Jacqueline Melo/Pressenza.com

“Being an affected woman in a place like that is complicated. Because the ones who have a voice are the men. We, women, are the last to be heard. If we don’t get together, we can’t succeed.”

Leandra reports that before the rupture, the women used to go out, and now they spend their days inside the house. “What if it’s a woman who doesn’t like to go to the bar? Who likes to go fishing, like many here in the community? Many ponds that have fish are on farms. Not all of them can go fishing, they must have a permit. Not in the river, the river is free. We lost this little ladies’ corner.”

Ecotechnologies: would it be possible to think about removing the mud from the rivers?

Especially in the last decades, the mining industry has been depositing large volumes of potentially toxic metals in riverbeds, contaminating the water and animals, turning them improper for use and consumption.

Professor at the Federal University of Ouro Preto (Ufop) and coordinator of the Environmental Education and Research Laboratory (Lauepas), the architect and urbanist Dulce Maria Pereira supports the mud removal by the mining companies.

“They [Vale and Samarco] stood their ground, saying that they would not remove the mud because that could do more harm to the river. This is not true because the mud will stay there for an indefinite time. […] You have awful changes, especially with arsenic, which causes mutations in fish. There is a ‘mixing’ of these materials and metalloids with the inorganic material on the river bottom, and huge changes are created in this habitat by leaving the mud in place.”

The professor recognizes that the processes needed to remove the mud might cause damage, but she argues that the river, unfortunately, is “virtually dead” from the mud by now. “So, you remove and leave the river alone, and then it will gradually recover over many years. In 30 years from now, we’ll look at the problems of the mud, but we could be looking at a reborn river,” compares Dulce, advocating for the ecotechnology potential — a science that integrates the fields of ecology and technology, focusing on sustainable solutions, seeking to reduce the environmental impacts.

“Rather than taking people out of contact with the potentially toxic metal, they could take the metal out of those places where people are. This goes through the ecotechnologies. A mining company the size of BHP, Vale, and Samarco saying they can’t remove the mud… That would be the ‘Elementary, my dear Watson’ that should have happened and that’s it,” ponders Dulce Maria Pereira.

“The companies, as big as they are, could vacuum this [the mud] with their eyes closed. You know that I’m into those technical fields, so, I name what they do as necroengineering, death engineering, which is like necropolitics. Why? Because it’s not engineering for life.”

The necroengineering mentioned by the professor relates to the low-quality engineering that causes visible and grotesque risks for the environment and local richness treatment. Through the use of inadequate technology, therefore, the necroengineering goes in the opposite direction of the technological possibilities that exist in contemporary engineering.

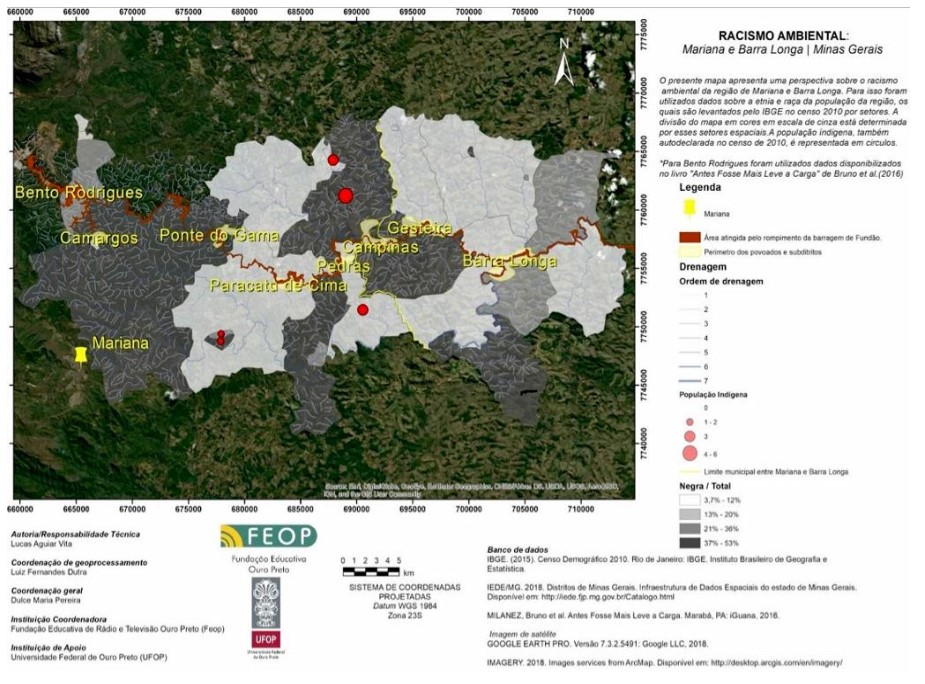

Neo-extractivism and Environmental Racism

The process of mineral extractivism arises in the context of conquest and colonization of America and is consolidated with the globalization of capital. “Extractivism and neoextractivism are inseparable from capitalism, it is a structural characteristic. And along with this characteristic is added the colonialist, racist, patriarchal logic itself,” points out lawyer Larissa Vieira.

“The extractivist model stimulates domination, this alienation process, from the moment it disregards, dehumanizes the people of the territories,” adds the lawyer.

For Professor Dulce Maria Pereira, the mineral extraction process is permeated by an “extraordinary perversity of environmental racism,” used to divide communities. “The houses that had less investment from the company, the lack of water, all this is worse for black populations. Apart from the communities of African matrices, who have literally lost the whole natural base of the foundations. It is an immense immaterial loss. The water, the grass, the plant, the air, which is how the material used for contact and for spiritual relations is organized.”

“They do not remove the mud from the river, which is awful, but why didn’t they remove the mud from the backyards? It is usually in the black backyards that there’s mud”, the professor asks.

Simone Silva, 44 years old, lives in Barra Longa, a city located about 60 km from Mariana. She is an art teacher and has a daughter, Sofia, 7 years old, who was contaminated by the toxic tailings when she was 9 months of age. In 2015, as Simone will never forget, the municipality was taken over by the mud from the rupture of the Fundão dam in Mariana.

“As long as I live, I will keep up this fight and resistance, which is to give a voice to my suffering people, to those affected by dams, especially black women. If I can occupy a place of speech today, in a classroom as a black teacher, it is because others came before me and made these struggles. How many drops of blood, and how many pieces of meat were cut in a public square so that I could speak today? This didn’t come on a silver platter.”

Simone became a militant of the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB, in Portuguese) after the crime of Samarco, Vale, and BHP. She does not fight only for the cause of health treatment for her daughter, but for the entire community where she lives. “You do not campaign only for yourself. There are other Sofias along the Rio Doce basin.”

Barra Longa (MG) – Gualaxo do Norte River, after the tragedy caused by the rupture of the Fundão Dam, of the Samarco mining company (SOURCE: José Cruz/Agência Brasil. 10/31/2017)

“Justice is a money-making machine for murderers and criminals. Never for the victims: justice only exists to take away rights and punish them. Because in this process of the mining companies, the victims come to occupy the place of the villain, while the mining companies are placed in the victim’s dock. The roles are turned upside down in this case of being affected by mining companies.”

“I even hope that it comes to the company asking people for forgiveness in such a process. That will ease a lot of people’s souls. That alone is a fundamental thing. Look at the way these people are treated by the companies, by their lawyers, by everybody. […] And there is disqualification. I was in several public hearings where I saw how they disqualified people. And that is quite serious.”

The future of affected women

“Mining knows no boundaries, from the point of view of its strategies. For example, it is not by chance that they don’t hire people who live in the same town where they mine so that they have no knowledge of the current processes, and even less of what is designed for the future […]. There is the exercise of a manu militari, of a technical and technicist power that disqualifies the local powers. And promises, seduction, that today we would talk about the fake news about mining. People get very intoxicated with the possibility of a development that never comes,” argues Professor Dulce Maria Pereira.

According to her, the accrued rights have been taken away, such as the right to water, remedy, health treatment, and to housing. She believes that if there is a serious action by the State and the mobilization of the affected people, with the engagement of intellectuals and environmentalists, “there will be a possibility of retaking the territory, with much more environmentally appropriate techniques and practices.”

Hairdresser Maria de Lourdes talks about her short and long-term wishes for her Taquaras. “I wanted us to be happy again. I wanted them to bring resources for us, an outdoor gym for women. A health center that we don’t have in our community. Here, if someone gets sick, either they get help from their closest neighbor or they die,” she says.

Resident of Barra Longa, Simone Silva says that little has been done in recent years as reparation measures and believes that the current scenario in the country contributes to this situation. “Seven years later, what has changed? What has happened? Has anything changed in this scenario? No. Only the manner, the ways, the violations of rights, the withdrawals of rights have changed.”

In her perception, there is also a lack of recognition by society itself in relation to the struggle of those affected by dams. “People don’t understand what militancy is, what a social movement is. For many people, it’s just a bunch of vandals, that sort of thing. Because the way people see the movement, unfortunately, is the same, especially in this particular moment that we are going through in Brazil. So, the movement, today, is more vandalized and badly seen.

The miner Ivone Pereira also talks about the withdrawal of rights of those who live in her community. “I wish that Vale had mercy on us. What it needs to do now – because it has already taken away all our rights – is to send a helicopter and drop a bomb to finish us off for good.”

For Leandra Moreira, a quilombola fisherwoman, the mining companies should have more consideration for the affected people and communities. She dreams of entertainment options for her community, besides a soccer field for the boys, sewing and painting classes, tractor driving, farming, vegetable garden, and “candy making” courses.

“To do justice, they have to know where they went wrong. Many times, Vale doesn’t even know, they say one thing to one person and something else to another. To do justice in my community, they would have to come here and see what we’ve been through. They’d have to come and bring water to everyone, to everyone’s cattle. Provide a recreational space for the community. Since they destroyed the river, they could try to improve the coexistence and the environment here,” adds Leandra.

Although still very shaken, Fernanda Soares, a saleswoman from Shopping da Minhoca, talks about the importance of hope for a better future for the affected people. “We have at least the hope of dreaming that one day there will be a recovery [of the river], if not total because it’s almost impossible, but at least a little bit, but if we let go, then we’ll have nothing. […] Because dreaming is free.”

Translated by Edmundo Dantez. Proofread by José Luiz Corrêa.